Like lots of different individuals, I loved Joachim Trier’s “The Worst Individual within the World,” a younger girl’s coming-of-age story that’s additionally a spiky romantic comedy of kinds. However the motive I can’t cease fascinated with this film (which I can’t talk about additional with out risking spoilers, so be warned) has to do with its standing as a Gen X midlife cri de coeur.

The complete cry — appropriately laced with self-mockery, self-pity and extremely particular pop-cultural references — arrives in a single devastating scene close to the tip of the movie. Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), a graphic novelist who just like the director is in his mid-40s, is dying of pancreatic most cancers. Julie (Renate Reinsve), the movie’s official protagonist, who had earlier damaged his coronary heart, comes to go to him within the hospital. She finds him taking part in livid air drums as “Again to Dungaree Excessive” by the Norwegian death-punk band Turbonegro blasts in his headphones.

“It’s such a visit simply to outlive,” the singer howls, and Aksel is preoccupied with issues of life, demise and in style tradition. He tells Julie that he spends most of his time listening to acquainted music and rewatching his favourite motion pictures, together with “The Godfather,” “Canine Day Afternoon” and the movies of David Lynch. “The world I knew has disappeared,” he laments.

What was that world? It was “all about going to shops.”

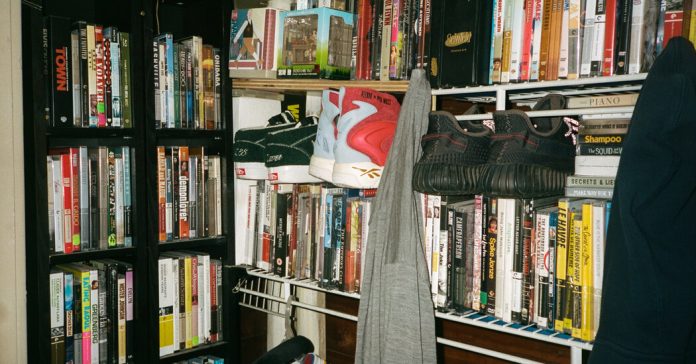

That description isn’t meant to trivialize his youthful pastimes and passions, however fairly to convey their magic and which means to a millennial whose major expertise of purchasing is more likely to encompass clicking on an icon fairly than rifling via bins. Aksel goes on to rhapsodize concerning the document, comic-book and video emporiums he used to frequent.

His pilgrimage stops could also be specific to Oslo, however they’ve counterparts in each metropolis. Julie, who works in a bookstore and dabbles in writing, is hardly oblivious to the utility and allure of bodily media. However she doesn’t fairly perceive the extreme emotion — the longing, the which means, the sense of identification — that Aksel attaches to reminiscences of an earlier fashion of consumption. This isn’t essentially a distinction of style or sensibility. It’s extra a contrasting relationship with the fabric points of tradition, a unique way of life in a world of issues, and it defines the generational schism between them.

I do know which facet I’m on. I don’t consider myself as a client, however the reality is that in my time on this earth I’ve hardly ever been in a position to stroll previous a guide or document retailer with out moving into, or to stroll out empty-handed. I’ve surrounded myself with issues, essentially the most treasured of which have been scratched, scribbled in, lent out or given away. As Aksel says, “I’ve spent my life doing that — gathering all that stuff,” however not due to its financial and even its sentimental worth. These objects start as vessels of which means and tokens of style, however their acquisition turns into a type of compulsion, emptied of its authentic ardour. “I saved doing it when it stopped giving me the highly effective feelings,” Aksel displays. “Now it’s all that I’ve left: reminiscences of ineffective issues.”

I don’t utterly determine with Aksel. He’s kinder, cooler (it took me some Googling to determine that Turbonegro music), a number of years youthful and loads higher trying than I’m. But it surely isn’t sufficient for me to say, as individuals do nowadays, that watching him made me really feel seen. The impact was extra intimate, extra surprising, extra shameful, as if Trier had dumped out a laundry bag stuffed with my favourite classic band T-shirts on Aksel’s hospital mattress for the entire movie-loving world to rummage via. Seen? I felt smelled.

Not that that is all about me. What Aksel says to Julie confirms him as an particularly sympathetic and self-aware specimen of a recognizable, not at all times beloved kind: not a fan, precisely, however a extremely opinionated hybrid of connoisseur, collector and critic. You would possibly know a model of this man from the novels of Nick Hornby (or the movies tailored from them), notably “Excessive Constancy” and “Juliet, Bare.” Or perhaps from motion pictures by Kevin Smith, Noah Baumbach, Judd Apatow and different Gen X auteurs. He may very well be your older brother, your ex- or present accomplice, your finest buddy or the long-lost buddy you’re kind of in contact with on Fb. Your dad, even. However then once more, should you’re like me, the teenager spirit you odor could also be your personal

In actual life, this sort of particular person isn’t at all times a man. Well-liked tradition typically assumes as a lot, and assumes his whiteness, too, which is partly a failure of collective creativeness, and partly a matter of whose cultural obsessions are taken as consultant. Chuck Klosterman, maybe the emblematic white male cultural critic of his (which is to say my) technology, considerably inadvertently makes this level in his new guide, “The Nineties,” when he implies that the discharge of Nirvana’s album “Nevermind” was a extra important world-historical occasion than the autumn of the Berlin Wall.

In typical ’90s style, the declare is hedged with knowingness and booby-trapped with irony. Klosterman understands that there have been loads of individuals within the ’90s — and never solely in Berlin — who by no means cared a lot about “Nevermind.” The attraction and the annoyance worth of his guide come up from the identical supply, specifically his unapologetic, extravagant dedication to generalizing from his personal expertise. “The Nineties,” with the modest, generic subtitle “A E book,” is neither historical past nor memoir, however fairly makes use of every style as an alibi for the shortcomings of the opposite. In fact this is only one man’s recollection of the stuff he noticed, considered, listened to and purchased within the final decade of the twentieth century. But it surely’s additionally, Klosterman periodically insists, an account of what that decade was actually like, a catalog of what mattered on the time and in hindsight. You may argue with the second model — how are you going to write a cultural historical past of the American Nineteen Nineties with out a lot as an index entry for “Angels in America”? — however not a lot with the primary. What the ’90s meant is open for debate. What the last decade felt like, perhaps much less so.

That is what makes Klosterman, who was born in 1972, a cheerful, mainstream American counterpart to Aksel’s gloomy, alternative-minded Nordic mental. They’re each ’90s guys, pushed to clarify one thing that appears at risk of being forgotten or misunderstood to individuals who weren’t there. To a level it’s the identical one thing, however not fairly the one thing both one thinks it’s. Klosterman seeks to light up the fact of a novel and essential interval; Aksel tries to share with Julie the sources of his personal sensibility. However the cultural reference factors are pink herrings. The deep motive is a longing to arrest and reverse the motion of time, to get well a few of the ardor and bewilderment of youth.

The belongings you liked while you had been younger won’t ever be capable of make you younger once more. The reluctant acceptance of this truth is the supply of nostalgia, a dysfunction that afflicts each trendy technology in its personal particular approach. Members of Era X grew up beneath the heavy, sanctimonious shadow of the newborn growth’s lengthy adolescence, amongst crates of LPs and cabinets of paperbacks to remind us of what we had missed. Simply as child boomers’ rebel towards their Despair- and war-formed mother and father outlined their kinds and poses, so did our impatience with the boomers set ours in movement. However I’m not speaking a lot a few grand narrative of historical past as about what Aksel would possibly name the ineffective stuff — the objects and devices that kind the infrastructure of reminiscence.

5 Motion pictures to Watch This Winter

Each cohort has these. A CD in a plastic jewel field isn’t intrinsically extra poetic than a vinyl LP in a cardboard sleeve. On the web and in tv reveals like “PEN15,” a sturdy millennial nostalgia fetishizes AOL chat rooms, Dance Dance Revolution, Tamagotchis and different issues that I used to be already too previous for the primary time round. Gen Z will certainly have its flip earlier than lengthy, even when its attribute cultural pursuits don’t appear to be manifested in bodily objects.

And that’s the substance, so to talk, of Klosterman’s relentless cataloging and Aksel’s lamentation for misplaced document shops. The digitization of tradition — the abstraction of all these lovely issues into streams and algorithms — feels to many people like a everlasting loss. What sort of a loss might be arduous to specify, since there may be additionally clearly a profit. Within the previous days, Aksel may not have been in a position to watch “Canine Day Afternoon” over and over. He might need needed to wait till it confirmed up at a revival home, or till the earlier buyer returned the one VHS copy to the video retailer. Now he can stream “Again to Dungaree Excessive” on a playlist along with his different favorites. Klosterman can watch any episode of “Seinfeld” or “The Simpsons” any time he needs.

And so can I. Why isn’t this consoling? Why do I, like so lots of my colleagues, mourn the passing of issues that aren’t even lifeless? The top of flicks, or at the very least of moviegoing, has been declared and decried (and in some instances celebrated) with growing depth via the rise of streaming platforms and the pandemic-assisted shrinking of theater audiences. The peril is actual, however which will solely be to say that the applied sciences of cultural consumption are at all times altering, and that the artwork varieties that circulate via them are likely to wax and wane in unpredictable cycles. Individuals proceed to learn, watch, hear, browse and search out not solely distraction and diversion, but in addition sources of which means and connection. Younger individuals have a tendency to take action with a particular avidity, typically as if their lives had been at stake.

I do know that feeling. I miss that feeling. However it might not, at backside, have a lot to do with music or books or motion pictures in any respect. Aksel doesn’t title Woody Allen amongst his favorites (although Allen’s affect on “The Worst Individual within the World” is straightforward to identify), however he does paraphrase certainly one of Allen’s well-known strains. “I don’t wish to dwell on in my work,” Aksel says. “I wish to dwell in my flat.” With Julie, and with their books and data and DVDs. What makes all these objects ineffective is that they lack the ability to make that doable, which is paradoxically why individuals like Aksel accumulate them within the first place. As he says: “It’s not nostalgia. It’s worry of dying.” Younger individuals don’t perceive this. They may.