There are many reasons to feel hopeless when it comes to the prospect of Israeli-Palestinian peace.

The sheer scale of death and devastation, first wrought by Hamas’ massacre and then by Israel’s intensive military assault on the Gaza Strip, has hardened opinions on both sides, fomenting grief, anger and desire for vengeance with no clear end point.

Still, senior figures closely involved with past attempts to resolve this most intractable of impasses have told NBC News that, in this moment of tragedy, there may be opportunity — and even hope.

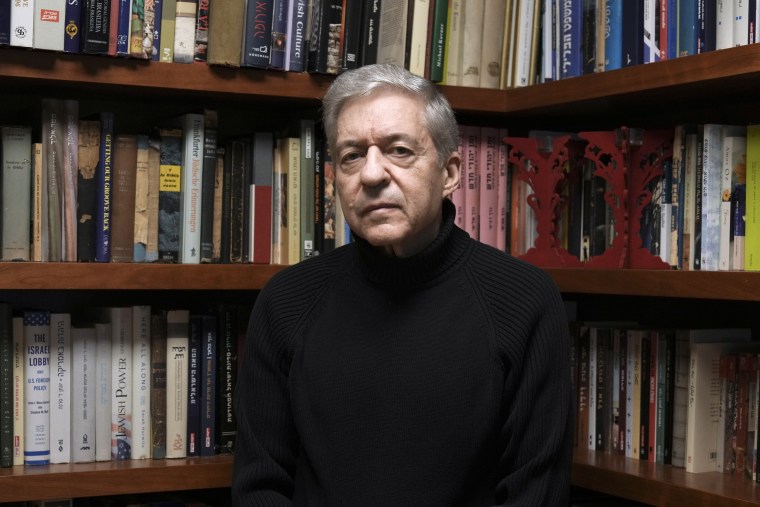

“It’s a big crisis — and crises create opportunities,” said Yossi Beilin, a veteran Israeli politician and peace negotiator whose backchannel discussions led to the Oslo Accords. This was a series of landmark agreements between the Palestinians and Israelis in the 1990s that mapped out a route to peace but ultimately failed on their promise.

While Beilin doesn’t kid himself about the scale of the challenge for those who seek a negotiated peace between the Palestinians and Israelis, he and others say one crucial thing has changed. To an extent not seen in decades, the eyes of the world are focused on Israel and the Palestinian territories — a patch of land barely larger than Massachusetts. And, whatever their political inclinations, few believe that the previously tolerated status quo can be allowed to continue.

“The world had given up on us,” Beilin said. “But Oct. 7 changed everything.”

Before that day, the issue of Israel and the Palestinians was languishing in a stalemate: Israelis felt unsafe from attacks by rockets and lone-wolf Palestinian militants. Gazans were trapped by a 16-year Israeli land, air and sea blockade that crippled the economy and crushed their hopes for the future. And Palestinians in the occupied West Bank were left to fend off Israeli settlers encroaching on their land, in tense altercations that regularly flared up into violent clashes.

But with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu assembling the most far-right government in the Jewish state’s history, and Hamas, a banned terror group in the United States and Europe, controlling Gaza, the prospect of compromise and moderation had scarcely felt farther away.

“People said the status quo is sustainable, and the issue of Palestinian-Israeli peace can be indefinitely put on the back burner,” said Omar Dajani, legal adviser to the Palestinian negotiating team at the Camp David summit of 2000. “All of that has been — for good and bad — blown out of the water by all that’s happened since Oct. 7.”

As gruesome as the war has been, it has spurred Western leaders to once again start talking about a “two-state solution.” This goal, widely considered moribund for at least a decade, is generally accepted to mean a single Palestinian state covering Gaza and the West Bank, with East Jerusalem as its capital.

“A two-state solution is the only way to guarantee the long-term security of both the Israeli and the Palestinian people,” President Joe Biden posted on X on Nov. 28 in one of his now often-repeated calls for such an outcome. He went further, saying this was essential “to make sure Israelis and Palestinians alike can live in equal measures of freedom and dignity,” adding: “We will not give up on working toward this goal.”

While the leader of Israel’s most important and closest ally advocated for a two-state solution to help Israel and the Palestinians emerge from decades of bloodshed, some senior Israeli officials have been increasingly vocal in their opposition to such plans. Israel’s ambassador to the United Kingdom told NBC News’ British partner, Sky News, that her country would not accept an independent Palestinian state when the war with Hamas ends.

“Absolutely no,” she said when asked about the possibility.

Netanyahu has struck a similar note.

“I destroyed the Oslo agreements. I thought they were a terrible mistake and I still think that,” he said during a press conference Dec. 16. “I am proud of the fact that I prevented the emergence of a Palestinian state.”

Jan Egeland, who was the lead diplomat for the Oslo Accords during his tenure as deputy foreign minister of Norway, says that a key ingredient that allowed those talks to move forward 30 years ago, was leadership. The Palestine Liberation Organization — then a feared terrorist group threatening Israel by hijacking planes — approached Norway seeking a way out of the stalemate.

A new Israeli government, led by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres had just stepped into power in 1992. They signaled that they were interested in exploring the PLO’s overtures, and began the secret talks that led to the Oslo Accords. Then-President Bill Clinton presided over the signing of the accords, and the U.S. invested time and resources to implement the peace process.

“The problem today is that we have nothing near the same leadership on both sides as we had at that time,” Egeland said. Israel’s ruling coalition includes what he describes as “the most extremist government in Israel’s history. It’s filled with racists and extremists.”

“These are people who do not belong in any government in any civilized nation,” he added.

On the other hand, “Hamas has the killings of the seventh of October on their conscience and so much other things,” he said, referring to decades of rocket attacks and suicide bombings on Israeli civilian targets.

“I don’t think Netanyahu will be at the table. I don’t think Hamas will be at the table,” Egeland said.

Any attempt at a peace process “will depend on the international community,” he said, steered by the United States, the European Union and Arab nations.

“The U.S. has sat on the fence now for so many years without playing the leadership role that they should,” Egeland said. “They must come down from the fence and lead a real peace process like the U.S. did in the 1990s.”

For now, the Biden White House has plenty of critics in pro-Palestinian circles for employing an ostensibly bold rhetoric while still giving Israel more than $3 billion a year, supplying weapons and munitions and offering diplomatic support.

That the agreements in Oslo failed to lead to peace, according to Egeland, had to do with wider resistance to the process. “The enemies to peace were so strong,” he said, with extremists on both sides, including the far-right Israeli who assassinated Rabin in 1995 over his role in the talks.

Today, opinion on the ground is increasingly polarized.

Poll after poll suggests that Jewish Israelis overwhelmingly support the war — 87% in the latest survey by the Israel Democracy Institute think tank earlier this month. And NBC News journalists interviewing hundreds of Israelis since the war began have been told, even by those mourning Palestinian casualties, that destroying or at least defanging Hamas is essential for their own national security.

Some 1,200 people were killed and almost 240 kidnapped in that Hamas assault. Since then, almost 22,000 Palestinians have been killed in the ensuing Israeli bombardment and invasion, according to local health officials backed up by officials in the U.S. and the United Nations.

Meanwhile, a poll conducted in the West Bank and Gaza during the 7-day truce in November, and released Dec. 13 by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, a respected polling institute based in the West Bank city of Ramallah, found that most Palestinians supported Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack. Just over 72% of Palestinians believe Hamas’ attack was “correct” given the Israeli response. The poll’s 1,231 respondents were interviewed face to face in the occupied West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Many Palestinians “feel that the prisoner gave back to the Israelis what the Israelis have been giving to them,” Hanan Ashrawi, a veteran Palestinian politician, said in an interview with NBC News last month. “I personally do not condone any violence against civilians, but I also believe that what the Palestinians have been going through has been totally disregarded by the rest of the world,” she said, referring to what she and other pro-Palestinian voices see as decades of mistreatment by Israel, enabled by its international backers.

“The victim has to lie down and die quietly, otherwise they will be called a terrorist,” Ashrawi said.

Support for Hamas has tripled in the West Bank, and increased slightly in Gaza. Despite this, the majority of Palestinians still do not support Hamas as a political party. In Gaza, which Hamas rules, support for the group stands at 42%, a slight uptick from 38% three months ago. Support for a two-state solution has risen slightly, from 32% before the war, to 34% — within the poll’s margin of error.

Many Palestinians interviewed by NBC News say they don’t believe Israel’s official war goals of toppling Hamas and freeing the hostages, and think the war is instead a cover to ethnically cleanse Palestinians from Gaza. A fear that is not unfounded — expelling Palestinians from their land has long been an extremist position in Israel that has gained more mainstream prominence during this war.

While some see the hardening opinions as signs that a two-state solution may be beyond reach, others, such as Beilin, disagree.

“It is recommended not to read polls during war; people are full of hate,” he said, adding that if Israeli and Palestinian leaders “come back in two years’ time with a peace treaty, there will be huge majorities to support them.”

Beilin, Dajani and other current and former Israeli and Palestinian officials interviewed by NBC News over the past two months have sketched out one possible path to peace: oust Hamas from power, hand Gaza to an international coalition perhaps led by neighboring Arab powers, rebuild Gaza’s infrastructure and democracy, and have a revitalized Palestinian Authority govern a unified Palestinian state covering Gaza and the West Bank.

That plan is “something which is worth considering,” former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak said in an interview with NBC News in late October. “I cannot promise you that it’s practical. It’s up to the minds of the different players. But it deserves being checked out,” he said.

There are countless unanswered questions: How to reassure Palestinians and Israelis that they are safe; what to do with Israeli West Bank settlements deemed illegal under international law; how to enable the Palestinian Authority to govern Gaza when it barely has a handle on the West Bank; and how to handle the millennia-old quandary of Jerusalem, a city dotted with holy sites — and strife — for Jews, Muslims and Christians.

“There’s definitely room for hope, so long as we bear in mind that hope and optimism are different things,” Dajani said.

For Egeland, it’s not so much hope but horror that could force the hand of the international community to act. He says the atrocities of Oct. 7 and the “bloodletting” that followed in Gaza have convinced the international community that “the occupation cannot continue like this, the siege cannot continue as it has been, the warfare cannot continue.”

“I don’t think the world will let the Israelis and Palestinians kill each other every second year in this crossroads of civilizations, which is Israel and Palestine, forever,” he said.