Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is experiencing yet another mass coral bleaching event due to heat, the country’s government confirmed Friday.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, which oversees efforts to preserve and protect the reef, said a widespread bleaching event is unfolding that is “consistent with patterns of heat stress that has built up over summer.”

Scientists with the Australian Institute of Marine Science said this is the fifth mass bleaching event to hit the Great Barrier Reef since 2016.

Bleaching events are a major threat to the health of coral reefs around the world. Coral bleaching occurs as a result of abnormal conditions, such as when ocean temperatures are unusually warm or cold, or when ocean water is more acidic than normal. In response, corals expel tiny photosynthetic algae that live in their tissues, causing the normally colorful marine invertebrates to turn white.

Bleaching does not necessarily kill corals, but the process causes reefs to become more susceptible to disease. Corals can recover from widespread bleaching events, but when they occur frequently, scientists have said it is harder for reefs to bounce back.

Studies have shown that climate change is elevating ocean temperatures around the world, making coral bleaching events more frequent. Last year, global sea surface temperatures shattered records, spiking as multiple bodies of water experienced “unprecedented” and long-lasting marine heat waves.

El Niño conditions were also a factor in 2023, compounding background warming from climate change. El Niño, a natural climate cycle characterized by warmer-than-usual waters in the Pacific Ocean, typically increases average air and sea temperatures and can have a significant effect on rainfall, hurricanes and other severe weather.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority said the current mass bleaching event is consistent with similar reports of bleaching across Northern Hemisphere reefs as a result of El Niño conditions in the Pacific Ocean and elevated ocean temperatures exacerbated by climate change.

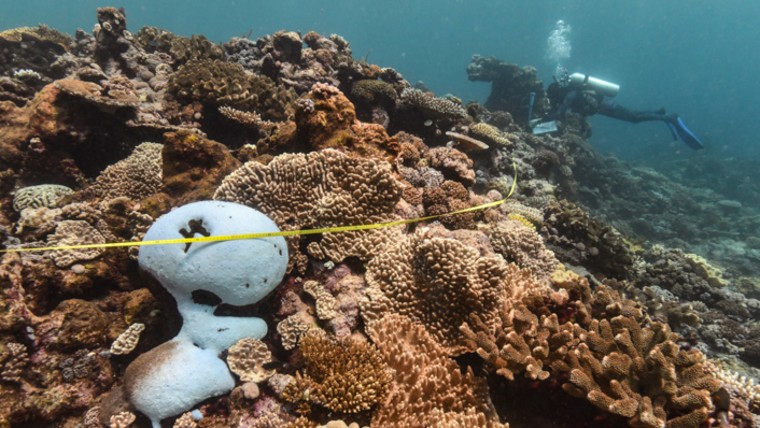

Together with scientists at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, the agency conducted aerial surveys that covered nearly two-thirds of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. These observations included more than 300 inshore, midshelf and offshore reefs, in the southern and central regions, according to the scientists.

While the groups were able to confirm that a mass bleaching event is underway, further study and in-water assessments are required to understand its severity and potential impacts.

Researchers are expected to conduct further aerial surveys over other parts of the reef when weather conditions are suitable.

So far, the researchers noted that heat stress does not appear even across the reef.

“As the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem is so large, the size of Italy, the heat stress across it isn’t uniform,” Neal Cantin, a senior research scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, said in a statement. “As a result, we are seeing differences between reefs with respect to the number of corals that are completely white.”

The first recorded bleaching event at the Great Barrier Reef occurred in 1998, and a second was observed in 2002. After a 14-year gap, four others occurred in close succession: in 2016, 2017, 2020 and 2022.

Prior to these events, there was no other evidence of widespread bleaching events in the Great Barrier Reef’s 500-year coral record-keeping history, according to the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Officials said the results of aerial surveys and in-water observations will help government agencies understand conditions across the reef and how best to manage restoration efforts.

But David Wachenfeld, a research program director at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, said that protecting the Great Barrier Reef will require addressing its biggest threat: climate change.

“[T]o protect coral reefs like the Great Barrier Reef from climate change, we need strong global emissions reduction to stabilise temperatures, best practice management of local issues, and the research and development of interventions to help boost climate tolerance and resilience for coral reefs,” he said in a statement.