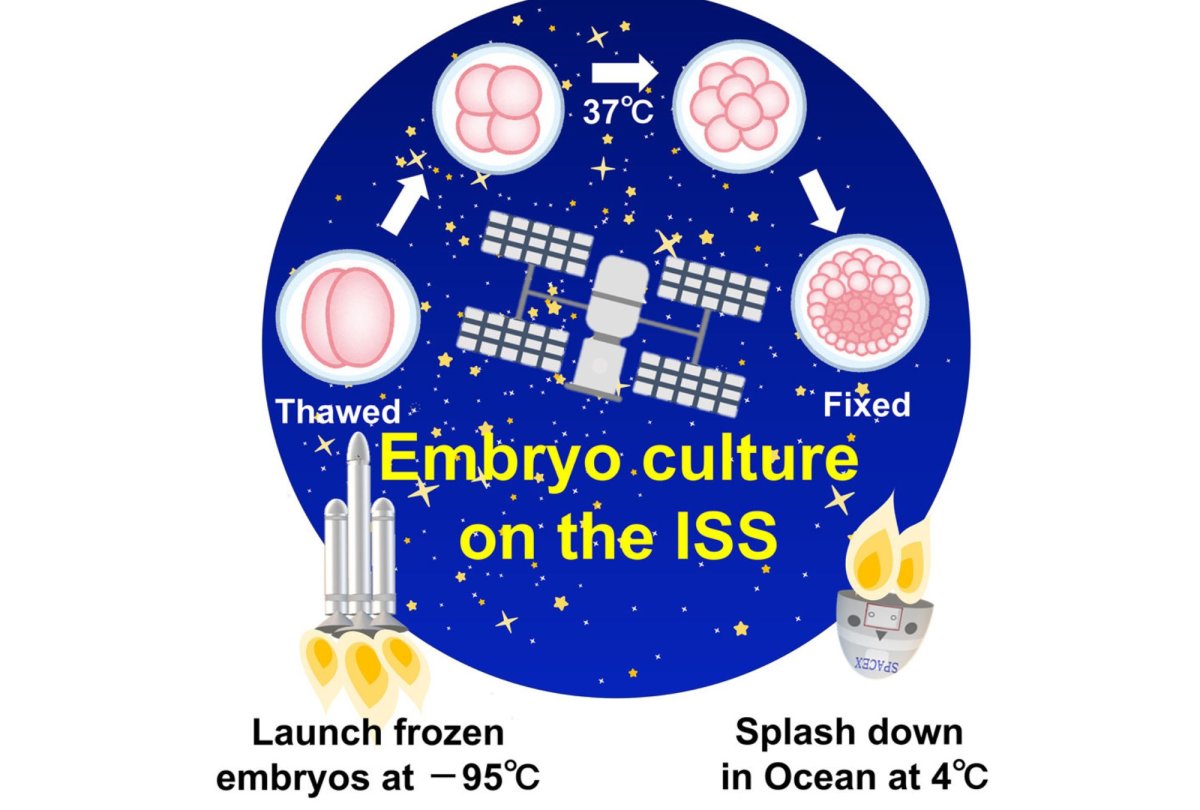

In a world first, embryos have been sent to space so that scientists can study how zero-gravity affects a growing fetus.

The mouse embryos were sent to the International Space Station to be raised by astronauts, with the scientists discovering that the embryos were able to successfully develop, according to a paper in the journal iScience.

This has huge implications for the future of human space travel and how reproduction and gestation are affected by zero-g, and marks “the world’s first experiment that cultured early-stage mammalian embryos under complete microgravity of ISS,” the authors of the paper said in a statement.

Teruhiko Wakayama/University of Yamanashi/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108177

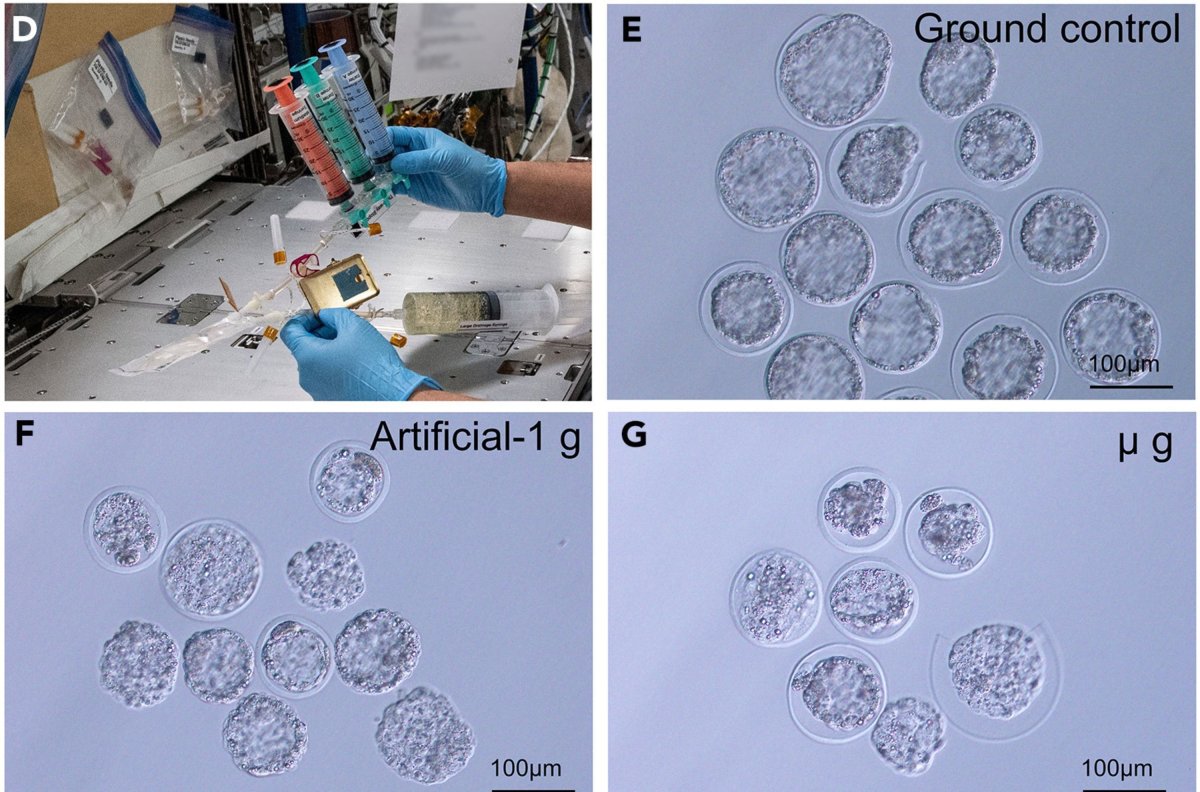

The researchers, from University of Yamanashi’s Advanced Biotechnology Centre and the Japan Aerospace Space Agency (JAXA), sent the frozen mouse embryos to the ISS—orbiting at a distance of around 400 miles above the surface—via a rocket in August 2021. Astronauts aboard the ISS then thawed the embryos, which were initially at the two-cell stage and grew them for four days, around a quarter of the 20-day gestation period for a mouse, at both artificial 1-g and zero-g.

They found that they developed normally into blastocysts, which are embryos that have differentiated into two cell types: the inner cell mass (ICM) or embryoblast, and an outer layer of trophoblast cells. The researchers then compared the development of the embryos with those cultured on Earth, finding that while those grown in space had a slightly lower survival rate, but were still successful at developing.

“The embryos cultured under microgravity conditions developed into blastocysts with normal cell numbers, ICM, trophectoderm, and gene expression profiles similar to those cultured under artificial-1 g control on the International Space Station and ground-1 g control, which clearly demonstrated that gravity had no significant effect on the blastocyst formation and initial differentiation of mammalian embryos,” the authors wrote in the paper.

It has long been wondered if the microgravity of space will impact the gestation of a fetus, which is a pressing question if humans are to further step toward the stars.

“There is a possibility of pregnancy during a future trip to Mars because it will take more than 6 months to travel there,” lead author Teruhiko Wakayama of the University of Yamanashi in Japan, told New Scientist. “We are conducting research to ensure we will be able to safely have children if that time comes.”

This study did not explore how the embryos developed post-blastocyst stage, however, which may come with a whole new swath of issues.

Teruhiko Wakayama/University of Yamanashi/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108177

Wakayama previously found in 2009 that microgravity affected a fertilized egg’s ability to implant in the uterus but did not affect the fertilization itself. Additionally, other experiments with pregnant rodents in space found that lack of gravity affected vestibular development during gestation—affecting the offspring’s balance and equilibrium—as well as impacts on fetal musculoskeletal development.

The authors say that much more research is required into how zero-g and space environments can impact the growth of fetuses.

Teruhiko Wakayama/University of Yamanashi/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108177

“Based on these reports and our results, perhaps mammalian space reproduction is possible, although it may be somewhat affected. Unfortunately, the number of blastocysts obtained from the ISS experiment was not abundant; and we have not been able to confirm the impact on offspring because we have not produced offspring from embryos developed in space,” the authors wrote in the paper.

“The study of mammalian reproduction in space is essential to start the space age, making it necessary to study and clarify the effect of space environment before the ISS is no longer operational.”

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about embryonic development? Let us know via [email protected].

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.