On a cold, drizzly January day in 1987, 35-year-old Lita McClinton Sullivan puttered around in her housecoat in her beautiful townhouse waiting for the day to unfold. She hadn’t slept well, anxious about going to court that afternoon.

At 2 p.m. in an Atlanta courtroom, a judge would make a pivotal decision about the division of assets in her multimillion-dollar divorce from James Vincent Sullivan.

She could feel the end coming. The turmoil of the 10-year marriage weighed heavy on her shoulders. She thought about Jim, rattling around in his 17,000-square-foot mansion down in Florida.

He’d grown into a terrifying bully, and she could hardly remember those early days when he, a handsome white man a decade older than her, had shown up with his quirky Boston accent and swept her off her feet.

At the time, her family had hoped the flame would burn out; Lita’s parents knew what their daughter would be up against as the Black half of an interracial couple in the South. Not to mention, they never liked Jim…he was brash and obnoxious, disrespectful of Southern norms. But none of that mattered now.

Lita was close, so close, to finally being free.

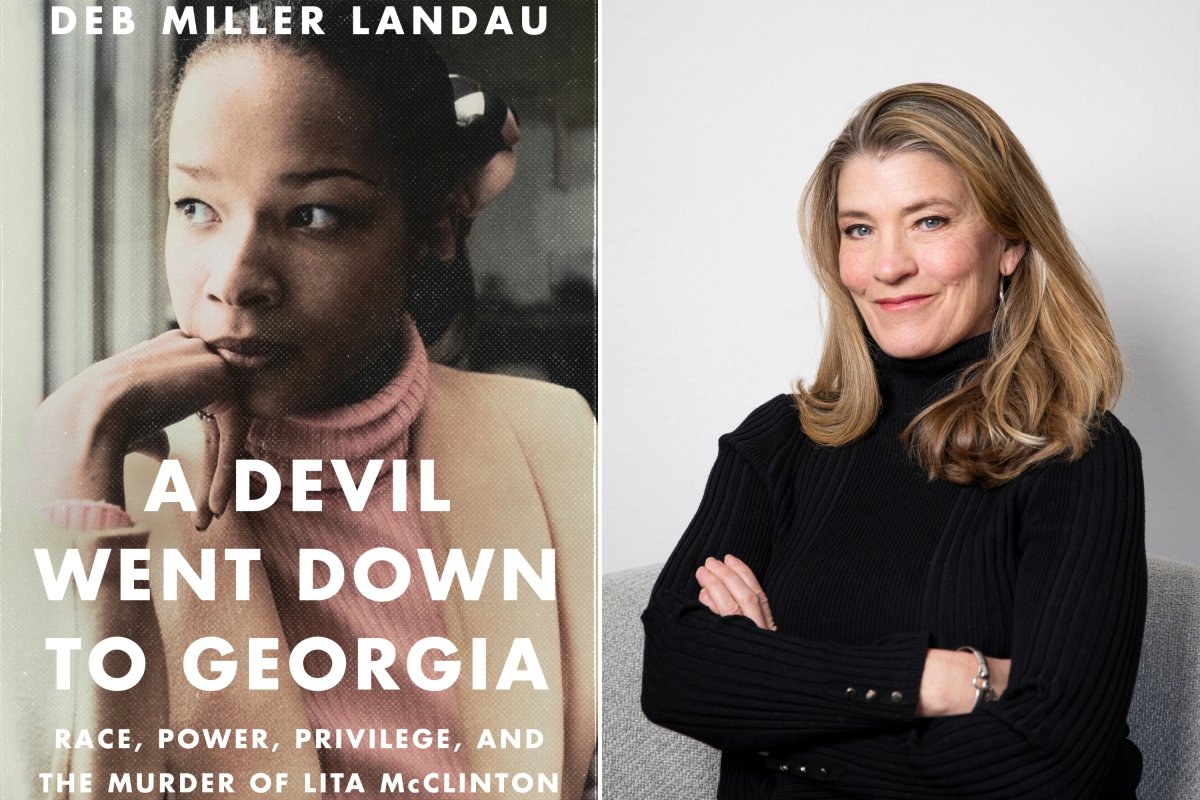

Newsweek Illustration/McClinton family/GBI/WPB Sheriff’s Office

The doorbell rang. It was early, just after 8 a.m., a Friday, the eve of a long weekend. Monday would mark the second-ever Martin Luther King, Jr. federal holiday. Lita’s best friend, staying with her for moral support, stirred with her young daughter in the upstairs guestroom.

The doorbell rang again. Lita tightened her pink silk housecoat and answered the door. “Good morning” Lita had to the delivery man, later described as white, six feet tall and scruffy, who stood on her stoop carrying a long white box.

Before she would’ve known what was happening, the man shoved the box in her hands, pushed his way into her foyer, reached into his coat pocket and pulled out a gun. He shot twice. One bullet missed, the other did not.

Today, as I write this, Lita would be 72 years old. There’s a good chance she’d have children, maybe grandchildren, who would be woven like perfect little threads into the tapestry of her close-knit family.

She’d be an aunt to her sister’s two boys—have watched them grow from tiny newborns to full-grown men. She would’ve been there to celebrate the family’s joys and help pick up the pieces after their sorrows.

Maybe she would’ve been a fashion designer or an interior decorator—something that satisfied her impeccable eye and naturally elegant taste. She’d have friends, so many friends. She’d throw parties, become even more involved in charitable events, take vacations, read books, grow old.

But she didn’t; she never got the chance.

I first wrote about this story for Atlanta magazine in 2004. At the time, Lita had been gone 17 years—and no one had been convicted of her murder. I didn’t know much about the story—only that it had been huge news at the time.

It was a case that shook the city, later the country, and still later the world. A Black socialite from a politically powerful Atlanta family, gunned down in broad daylight in one of the most upscale, whitest neighborhoods in Georgia.

The shooter, who delivered a dozen pink roses to Lita’s door, somehow vanished into the cold winter day despite being described by eyewitness neighbors.

Lita’s husband, James Sullivan, always a prime suspect, slipped by on his solid alibi and unwavering conviction that he was in Florida at the time of the murder and had nothing to do with it.

For a decade after the murder, the case went cold, unnervingly frigid. It became fodder for newspapers and magazines, was featured on television shows like Dominick Dunne’s Power, Privilege, and Justice, CBS’s 48 Hours, Extra!, FBI: Most Wanted, and others.

Journalists like me followed it for years, lawyers didn’t sleep, cops took it to their graves, and Lita’s family pushed and bent till they almost broke.

My article published and the world went on, but something about the story simmered in my soul.

Lita’s parents, Jo Ann and Emory McClinton, had moved me deeply. They were formidable people—literally everyone I ever spoke to about this story agreed with this sentiment and added words like, intelligent, kind, generous.

Lita’s mother, Jo Ann, spent a dozen years as a Georgia State Representative; Emory was head of the regional civil rights office for the U.S. Department of Transportation.

They were tireless advocates for civil rights, working within systems not designed to hear or honor Black voices. They found ways to bridge chasms—in boardrooms, in courtrooms, and at their dining room table. They were determined their children would grow up knowing their power, believing in their worth.

After Lita’s murder, they became unrelenting seekers of justice for their eldest daughter—unabashedly keeping pressure on authorities and questioning the criminal justice system every single slow and painful step of the way.

Years passed; I moved across the country away from Atlanta with a banker’s box full of files upon whose lid I’d scrawled “Sullivan” in black Sharpie. The contents included court documents, handwritten interview notes, business cards from long-ago district attorneys, lawyers, and fellow reporters, and a photo of Lita given to me by her parents.

In it, Lita looks so intelligent, beautiful, pensive that it now graces the cover of my book. I’d periodically pull that photo out and wonder what she was thinking in that moment, what she thought in so many moments before and after that.

Sometimes I’d Google James Sullivan. I kept in loose touch with the McClinton family lawyers and their private investigator. I watched the news closely when the hitman, after spending 20 years in prison for manslaughter, was released.

Then, in 2020 as the world was in lockdown, George Floyd was murdered by police in Minneapolis. Outrage followed as people began shouting about how Black lives mattered, protesters flooded the streets only to be teargassed and harangued as angry mobs.

Through those fiery months, something profound shifted within me as I learned more and more about my own role, as a white person, in upholding white supremacist structures and ideologies.

I began thinking about Lita and the McClinton family and how, when I wrote my article 15 years prior, I felt both enmeshed and distant from Lita’s story.

In this new day of reckoning, I wanted to see it more clearly, to bring adequate justice to the telling of this horrific and brutal murder of a life cut short by the orchestrations of white greedy men.

I reached out to my old Atlanta magazine editor, and we talked for hours. Finally, around the middle of the call, he said in his slow Georgia accent: “Well, maybe it’s time to write a book.”

There’d been a reason I’d carried that box around, and the responsibility of reopening its lid felt both essential and monumental. As I sifted through all the papers, I began to slowly realize the story I thought I knew wasn’t the whole story.

The more questions I asked, the more questions I had. They led me back to Atlanta and Palm Beach, Florida. I spent countless hours interviewing cops and FBI agents, friends, and lawyers and reporters and members of the McClinton family.

I sat transfixed as a former prosecutor taught me about the law while making chicken potpie. I learned about the history of the Deep South over homemade Thai food with my old editor in south Georgia.

I spent hours with a private investigator in Palm Beach who spoke in F-bombs and enraptured me with memories. I got on calls with ex-cons and professors and lawyers and judges.

I had phone conversations with Lita’s nephew, who was in utero when his aunt was murdered, and shared hours at the dining room table with Lita’s mom.

I spent days combing through files and photos in the archives at the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, and I interviewed the hitman in a rented minivan in a desolate park deep in the North Carolina sticks.

Pegasus Books

While I didn’t find the answers to all my questions, by asking them through the lenses of today, I am finding new perspectives. Desmond Tutu said: “My humanity is bound up in yours, for we can only be human together.”

In the 37 years since Lita lived on this earth, humanity has done some reckoning—about the power imbalance between men and women, our subtle and not-so-subtle prejudices, how the wealthy can wield their wallets to circumvent justice.

We’ve learned domestic abuse doesn’t exist only in physical injury—that mental and emotional violence can be just as traumatic as black eyes and swollen lips.

And some say we’ve come a long way in righting the wrongs of historical racism, while others believe we’ve barely moved the needle.

Every single person I spoke to for my book, A Devil Went Down to Georgia, along with every single person who declined interviews, had been touched by this story and it continues to live deep within them, even all these years later.

In all my writing and research, in all the quotes and court documents, in the wrenching sadness and profound joy, I found Lita. And her life—and what it can teach us about ourselves—mattered then, and still does today.

Deb Miller Landau is an investigative journalist. She reopens one of Atlanta’s most notorious murder cases in her new book, A Devil Went Down to Georgia (Pegasus Books), publishing August 6, 2024.

All views expressed are the author’s own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at [email protected].

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.