Tablas Creek Vineyard started growing Rhone grapes like Syrah and Grenache in California back in 1989. The vineyard’s founders chose the Paso Robles area, along California’s Salinas River Valley, because its Mediterranean-like climate was well suited for what they wanted to grow. But that climate has changed considerably over the past 35 years.

“You can see definitely the trend towards average temperature being warmer, harvest dates being earlier,” Tablas Creek Proprietor and General Manager Jason Haas told Newsweek. Like most farmers and growers, Haas pays close attention to rainfall, temperature patterns and harvest dates.

Haas said the average harvest dates have moved a week to 10 days earlier over the past 15 years. And while this winter’s snow and rainfall have helped to replenish the state’s water supply, prolonged droughts have become more frequent over the decades, something that scientists say is consistent with a warmer climate.

Photo-Illustration by Newsweek, Source Photos from Tablas Creek Vineyard

“California’s always been a drought-prone area, but we’ve had a string of pretty bad droughts out here,” Haas said. “I’m actually more worried about water availability from climate change than I am from temperature change itself.”

Haas said he thinks a lot about the potential impacts of climate change, from the effects of drought and groundwater depletion to the increased risk of wildfires.

A recent study in the monthly journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment suggests that he is right to be concerned. Researchers at France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment assembled data from dozens of previous studies on how climate change affects grape growth and wine production and projected the likely effects under different warming scenarios in the coming decades.

Most wine growers can adapt to a certain degree of warming, the study found, but with greater temperature increases, some of the world’s best known growing regions could be in trouble.

“If you get even more warming, then the decrease in suitability for many regions is pretty abrupt,” study coauthor Gregory Gambetta told Newsweek. “It’s very worrisome for those local economies and for growers and the whole industry that surrounds it.”

In the more extreme warming scenarios in which the world fails to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change, the study shows, up to 90 percent of traditional wine-growing areas in Spain, Italy, Greece and southern California would be at risk.

The findings show climate change is a potentially serious threat to a crop that is an economic and cultural cornerstone for many agricultural regions of the world, challenging vineyards and wine companies to both adapt to hotter, drier conditions and find ways to contribute to climate solutions.

“The climate issue is probably one of the biggest threats to the industry going forward,” Michael Kaiser, executive vice president for the U.S. industry trade group WineAmerica, told Newsweek.

Wine Regions at Risk in a Warmer World

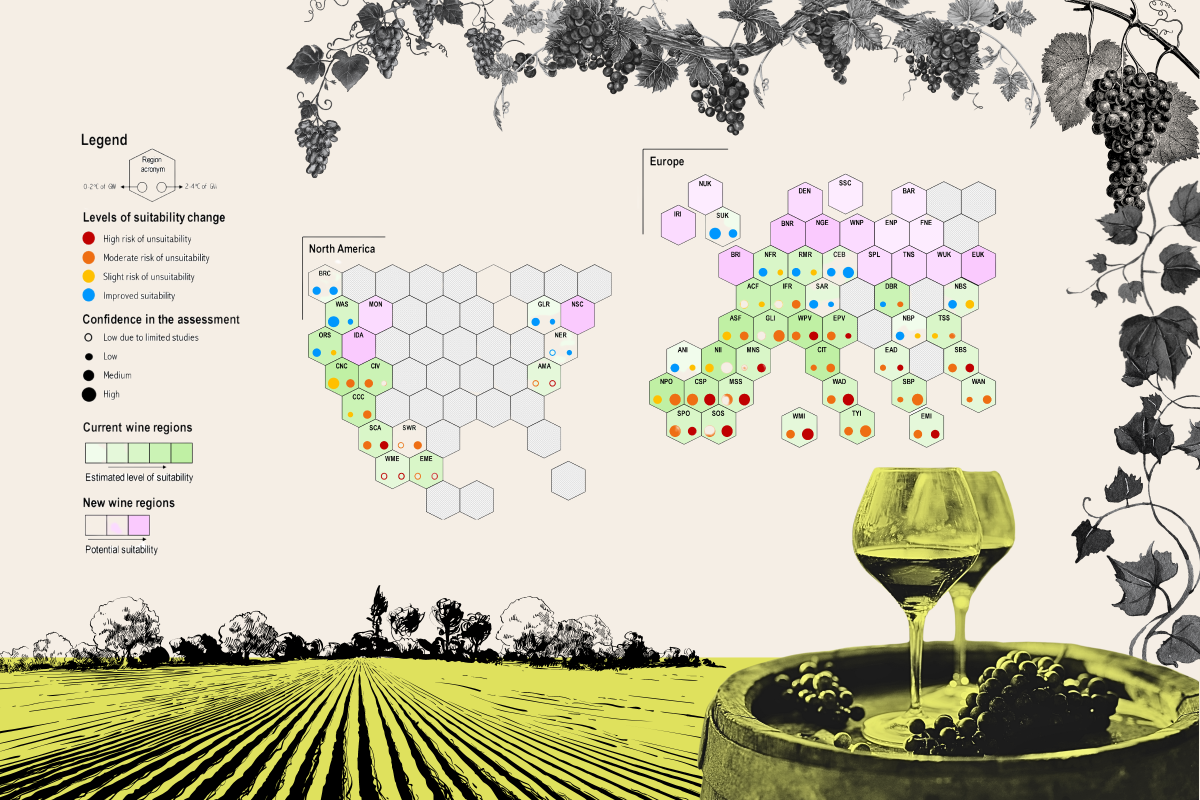

Gambetta studies the genomics of grapevines at the University of Bordeaux. He and his colleagues modelled climate change effects on grape growing under two warming scenarios over the rest of the century. In the first, warming is limited to 2 degrees Celsius (or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, in keeping with what the world’s major scientific bodies say is required to avoid the most dangerous effects of climate change.

Photo-illustration by Newsweek

“Most regions can buffer themselves against it through adaptation strategies that the growers can employ,” Gambetta said.

He stressed that grape vines are highly adaptable and grow in a variety of climates and local conditions around the world, giving growers options to switch to varieties better suited to changing needs.

Also, as some regions become too hot and dry to produce well, others will become more suitable for grapes. More northerly parts of Europe and the United Kingdom are now becoming more attractive as sites for future vineyards, for example (see the purple-shaded sections on the map graphic above).

If warming pushes beyond the 2 degrees Celsius threshold, however, the study finds that many major growing regions will likely suffer (those places are indicated by yellow, orange and red dots on the map).

“It doesn’t take a lot of time for that viticultural region to become a place that could be really challenging for growing grapes,” Gambetta said.

Grapes are the world’s third most valuable horticultural crop, after potatoes and tomatoes, according to the study. Some 80 million tons of grapes were grown worldwide in 2022, and about half were used to produce wine and spirits.

Vineyards in parts of Europe, including Spain and Portugal, are already feeling the heat, he said, and got a “wake-up call” from the extreme heat waves that struck Europe in 2022 and 2023.

“It was just so hot in Europe and so dry it was shocking,” he said. Many Spanish growers have been forced to switch from longstanding practices of dry farming to irrigation for vineyards. Over the past 25 years or so, Gambetta said, irrigation has grown from less than 10 percent of Spanish vineyards to almost 40 percent, a shift with implications for the broader water supplies.

In the U.S., growers are experiencing a wide range of climate change impacts, Kaiser at WineAmerica said.

California is perhaps most associated with wine production in the U.S., but WineAmerica says wine is produced in all 50 states—yes, even Alaska—with more than 10,000 growers, producers and distributors supporting more than 1.8 million jobs.

Kaiser said that while drought has been a concern for California, growers elsewhere have the opposite problem.

“On the East Coast there’s more extreme rain events that are happening, whether it be tropical storms or rain at the wrong time,” Kaiser said.

He explained how a grower’s options to switch grape varieties to match changing conditions can be complicated when a regional wine’s marketability is tied to a particular kind of grape and local flavor.

Courtesy of Tablas Creek Vineyard

The characteristic taste a wine gets from local environmental conditions can become integral to a wine’s value. Growers call it “terroir,” a term that stems from the Latin word for earth, terra. As the climate changes, some vineyards could find the terroir shifting beneath their feet.

For example, Oregon’s Willamette Valley, Kaiser said, has become identified with its pinot noir wines. Kaiser described the grapes there as “finnicky,” and a warmer, drier climate could be problematic.

“They branded themselves on something very specific and to have to switch and change all of that, that would be tough,” Kaiser said.

A Virtuous Cycle in Vineyards

Kaiser said many growers are aware of findings such as the ones in the recent study, but they are preoccupied with near-term challenges and making sure the next vintage comes through. His group hopes to encourage more conversation and longer-term planning about climate impacts.

“The industry, I think, needs to really try to think about where we are in five, ten, twenty years,” he said. “Some of the data coming out is kind of scary.”

He said many small growers and large companies are taking steps toward more sustainable production and operations, but open discussion about specific responses can get touchy. Adaptations such as changing grape varieties and growing practices, or putting vineyards in new locations, could risk divulging some of the proprietary information involved.

Two of the world’s largest wine producers appear on Newsweek‘s rankings of most trusted companies.

London-based Diageo, which owns more than 100 wine, beer and spirit labels, ranks 78th among the 82 companies in the food and beverage sector on Newsweek‘s list of the World’s Most Trustworthy Companies. California-based E&J Gallo Winery produces an estimated 3 percent of the world’s total wine output and ranked 31st among 50 companies in the food and beverage sector on Newsweek‘s ranking of the Most Trustworthy Companies in America.

Both companies declined to comment for this story.

At Tablas Creek, Haas is happy to talk about the steps his vineyard is taking to both make their vines more adaptable to climate change and to make the vineyard more climate friendly.

Haas is concerned that groundwater could become limited and is taking steps to make the vines able to grow without irrigation.

“We’re spacing [the] vines farther apart, where they’ve got more cubic yards of soil per vine, which allows them to be self-sufficient with what falls from the sky,” he said.

Tablas Creek was the first vineyard certified by the Regenerative Organic Alliance, an organization that promotes farming practices that can help build up the organic content of soil so that it holds more water and draws down carbon dioxide through natural processes.

Courtesy of Tablas Creek Vineyard

For Haas, that involves maintaining a herd of sheep (and a few alpacas) to keep down weeds in the vineyard while adding organic matter in the form of their droppings, and careful use of cover crops to create a virtuous cycle of soil carbon management.

“So, your soil becomes a repository for atmospheric carbon, and the greater the carbon content of your soil, the more water it holds, the better it resists heat spikes, and the more nutrients it helps build,” he explained.

As vines begin to produce buds and leaves, he rotates the sheep to graze among the adjacent woods, keeping down brush and reducing the fuel for wildfires.

Other growers frequently visit to learn about the benefits of regenerative farming, he said, and dozens more vineyards have now been certified. At least one large California estate holder, Jackson Family Wines in Santa Rosa, has announced a plan to switch all its vineyards to regenerative farming practices by the end of the decade.

Haas said those practices require attention and effort but do not necessarily add a lot of cost considering the substantial benefits for both growing grapes and selling them: Wine consumers want to know what’s behind the label they’re buying.

“I think people more and more want to know that the products that they support are being made, farmed in a way that’s consistent with what they think is the right way to do things,” he said. “There’s not a negative side to this at all.”

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.