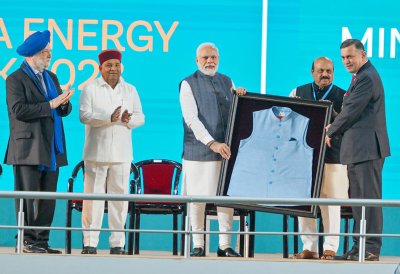

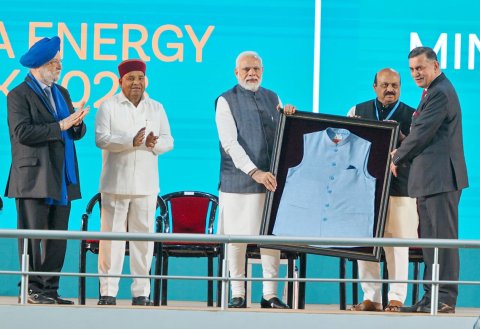

“Touch my vest,” Narendra Modi told a startled Newsweek team interviewing the Indian prime minister in his residence in New Delhi in late March. “Come on, touch it.” Modi challenged Nancy Cooper, Newsweek’s global editor in chief, to guess what the blue jacket was made of. Cooper suggested silk. “It’s recycled plastic bottles,” Modi said, clearly enjoying the reaction of his surprised guests.

The vest and the moment are vintage Modi: innovation, tradition, masterful messaging and, inevitably, some controversy. The vest was made popular by India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, whose great-grandson Rahul Gandhi is leading the opposition campaign to prevent Modi from winning a rare third term in elections next week. It became known as the “Nehru Jacket” and was a symbol of newly independent India’s national pride as well as a fashion statement adopted by The Beatles and Sammy Davis Jr. Unlike Nehru, who preferred beiges and grays, Modi wears his modified version of the garment in brilliant hues. Indian retailers began selling “Modi Jackets” to capitalize on the prime minister’s enormous personal popularity. And in 2018, when former South Korean President Moon Jae-in tweeted out his thanks for the prime minister’s gift of perfectly tailored “Modi Vests”—not “Nehru Jackets”—the controversy nearly broke the Indian internet.

PMO India

“Whatever you can rightly say about India, the opposite is also true,” the Cambridge economist Joan Robinson once said. Modi, like the country he leads, is full of apparent contradictions. A relentless modernizer, Modi embraces the past. He speaks with equal pride of digital payments, green technology and his role in an ancient 11-day ritual to bring a revered Hindu deity to life. Modi merchandises his brand like a celebrity with T-shirts, mugs and caps, and yet appeals to ordinary Indians by picking up trash from the beach or sweeping the streets. Perhaps uniquely among leaders of major powers, he wins praise from Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin and has warm relationships with both men. Modi’s campaign slogan calls for inclusive progress, yet many religious minorities feel excluded by his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party.

I feel negativity has a low shelf life…. On the other hand, positivity is perennial.”

– Narendra Modi

Partly because of these contradictions, Modi has a contentious relationship with the media and gives interviews rarely. India has tumbled on the World Press Freedom Index under Modi. And the prime minister sees himself as a target of hostile coverage by journalists who do not accept that India is both less liberal in ways that are important to the West and much better governed than at any time in its recent history.

Understanding an Indian prime minister has never mattered more. The country Modi leads is increasingly shaping the world we live in. Washington sees India as an important counterweight to China across the developing world. A globe-girdling Indian diaspora, cultivated for decades by Modi, has already reshaped Silicon Valley. Now Indian ideas, innovations and ambitions are poised to do the same in everything from finance and fighting poverty to space exploration. By 2075, the Indian economy is projected to surpass America’s and become the world’s second largest behind China. This also means that India is by far the biggest potential carbon emitter in the world and its choices about the future will likely play an outsized role in defining the destiny of our planet and the species we share it with.

During his 90-minute interview with Newsweek and in written correspondence, Modi tackled these issues and talked of his unbridled optimism about India. “I feel negativity has a low shelf life,” he said. “On the other hand, positivity is perennial.”

Modi says he channels his positive energy into his monthly radio program Mann Ki Baat (Talks from the Heart) that one survey said had 230 million regular listeners. The state radio show is one of the many ways the prime minister appears accessible to ordinary Indians and puts his personal stamp on myriad changes shaping their lives. To Western observers, Modi’s messaging tactics can come across as political theater, the squandering of public resources on the making of one man’s myth. What they miss is the revolutionary impact these tactics have had on people in a hierarchical society shaped by millennia-old caste structures, centuries of colonial exploitation and decades of rule by the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty whose charismatic leaders are dismissed by Modi’s followers as members of a Western-educated elite.

1 of 5

PMO India

Not every message lands the way Modi intends it. A Maan Ki Baat episode notched up the most dislikes ever on the BJP’s YouTube channel after the prime minister dished out advice on dog breeds but dodged a dispute over delayed exams.

Modi says he treats all communication with the Indian people as a two-way street. “A leader should have the ability to connect to the grassroots and get unfiltered feedback,” he said.

A magnetic orator who fills stadiums wherever he goes, Modi is coy about his speaking skills. “I didn’t even know that I am good at communication,” he said. Ask him about listening skills and he swells with pride: “I am god-gifted with this quality.”

India has run the world’s largest poverty-eradication drive in the last 10 years and has pulled 250 million people out of poverty.

Modi, who grew up relatively poor and traveled the country for years as a Hindu community organizer, says he has spent at least one night in each of about 80 percent of India’s 806 administrative districts, roughly equivalent to counties in the United States. “So I have direct connections almost everywhere, which helps me get direct feedback,” he said, driving home the point with a story about a man he met on his travels calling him at 3 a.m. about a rail accident when he was chief minister of the western state of Gujarat so it could be addressed immediately.

Whatever one makes of Modi’s messaging strategy, it appears to be working. Hundreds of millions of Indians are listening to Modi, tuning into his positive message and feel heard by him. India’s urban consumers are the most optimistic in the world, according to an IPSOS survey released in March. The national index score of 72, higher than any of the other 28 economies surveyed, “indicates consumers have confidence in the economy, jobs, personal finances and investments, now and for the future,” IPSOS said.

1 of 4

PMO India

PMO India

PMO India

Getty Images

Getty Images

It is easy to be optimistic about the Indian economy. Asia’s economic miracles have been built around a demographic sweet spot when the working age population reaches the point that dependents—retirees and children—form the smallest share of the population. Japan hit this tipping point in 1964. China in 1994. For India, already the world’s fifth largest economy, the sweet spot of a historically low dependency ratio won’t arrive until 2030 and it will last at least 25 years. This demographic destiny is one of the reasons Bhaskar Chakravorti, dean of global business at the Fletcher School of Tufts University, co-authored a Harvard Business Review article in which he recommended “Inevitable India” as an advertising slogan for the government in New Delhi, a play on the decades-old tourism campaign “Incredible India.”

The narrative-building apparatus around Narendra Modi has made him appear to be an indispensable figure in the inevitability of India.”

Bhaskar Chakravorti, dean of global business at the Fletcher School of Tufts University, echoing a critique of the Modi government economic claims

“The narrative-building apparatus around Narendra Modi has made him appear to be an indispensable figure in the inevitability of India,” Chakravorti told Newsweek, echoing a common critique of the Modi government claims about the economy. But demographics don’t tell the whole story of the economic promise of Modi’s India. In the past decade, Modi has transformed India’s infrastructure, building roads, bridges, ports, airports and digital networks at astonishing speed. A country that was once notorious for potholes, bottlenecks, crumbling terminal buildings and traffic snarls caused by cattle, is now competing with the best on many fronts. India’s ports are more efficient than America’s or Singapore’s with ship turnaround times of less than a day. It will soon boast the world’s third-largest metro network after China and Britain. A Venmo-like Unified Payments Interface connects 300 million users to a system that accounts for nearly half the world’s instant payments.

Modi’s tenure has ratcheted up the productive capacity of the world’s most populous country. Goldman Sachs cites these infrastructure investments in its projections of India’s explosive economic growth over the next half-century when it overtakes the United States. Goldman’s projections show the U.S. economy doubling in size by 2075 and China’s just about tripling. The Indian economy will grow 15-fold. The economic value of these investments understates their impact on the way Indians, like the Chinese and Japanese before them, see themselves. “India is undertaking a vast national project of state-building under Modi,” Ravi Agrawal, editor in chief of Foreign Policy magazine, wrote this week. “Modi is projecting an image of a more powerful, muscular, prideful nation—and Indians are in thrall to the self-portrait.”

Modi resists comparisons with Japan and China and talks instead of “human-centered development” woven around India’s traditional values. “India has run the world’s largest poverty-eradication drive in the last 10 years and has pulled 250 million people out of poverty,” he said. While that number is impressive, it is not unprecedented. China lifted about 800 million people out of poverty in the three decades before 2018.

And yet, the world needs India to pursue a different path from China’s. The future of the planet depends upon it. India’s gross domestic product is roughly the size that China’s was in 2007, in the midst of a surge of growth that made it the world’s second-largest economy. At roughly the same time, China emerged as the world’s largest carbon producer. Today China produces about 30 percent of the world’s carbon, nearly three times as much as the United States, which still has a much larger economy and much older infrastructure. America’s carbon footprint is shrinking, while China’s is still growing. India, already the world’s third-largest carbon emitter, is at a much earlier stage of its polluting capacity. Unless it changes trajectory, India will eat up 36 percent of the world’s remaining carbon budget—the total volume of carbon that scientists estimate all of humanity can produce and still keep global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius, according to a 2022 McKinsey report.

Getty Images

Fortunately for the planet, Modi has chosen a different course. “There is no contradiction between our physical infrastructure building and our commitment to fight climate change,” he said, rattling off an impressive list of initiatives, investments and goals that will help India get to net-zero emissions by 2070. McKinsey estimates these investments and policies will make for a potentially planet-saving transformation of India’s economic path. India’s carbon emissions per person should peak at around 2.7 metric tons in the 2030s, McKinsey projects. That means that even when the average Indian’s carbon footprint is at its largest a decade from now, they will still be producing only a third of the carbon emitted by a Chinese person today and a fifth of what an American produces.

This greener growth is but one facet of the contrasting roles India and China will play in the global economy. Western companies looking to move their supply chains out of the firing line of U.S.-China tensions are turning to India, with Apple being one of the first to open a plant there.

And yet China’s ambitions have loomed larger, and for far longer, in New Delhi than it has in any Western capital. In the 1950s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru turned down two offers of a permanent seat on the U.N. Security Council, not wishing to take China’s place on that body, according to the Wilson Center’s Cold War History project. India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar described those decisions and other efforts to placate Beijing’s Communist rulers as “India second, China first” in a speech this month.

Nehru’s deference to his powerful neighbor did nothing to prevent the relationship from deteriorating into a border conflict in 1962, which went very badly for India. Since then, China has been the central geopolitical preoccupation of every Indian prime minister. Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, broke with her father’s policy of Non-Alignment and signed a friendship treaty with the Soviet Union in August 1971, a month after U.S. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger made his historic visit to China.

Getty Images

While Modi still has close relations with Moscow, he has taken a considerably more assertive approach to foreign policy—and that has drawn him closer to the United States, which now views China as an adversary. “As President Biden has said, our relationship with India is one of the most consequential in the world,” a U.S. State Department spokesperson told Newsweek. “The United States supports India’s emergence as a leading global power.”

Modi has personally pressed Chinese President Xi Jinping to resolve their border dispute. And he definitely wants that permanent seat on the Security Council. In his sharpest shift from India’s proudly Non-Aligned past, Modi has joined the Quad, an alliance with Japan, Australia and the United States, whose unstated purpose is to counter China’s influence in the Indian Ocean and Pacific regions. “The Quad has established itself as an important platform for ensuring peace, stability and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific,” Modi said, playing down the Sino-centricity of its mission.

India’s many geopolitical and economic strengths are not the whole story. The government’s relationship with religious minorities appears to have gotten significantly worse under the ruling BJP, which Modi now leads. Modi’s supporters see Hindu nationalist policies as leveling the playing field, taking away privileges granted to Indian Muslims, Christians and others by colonial rulers and past governments after independence. Restoring what Hindus see as the status quo is key to both progress and national unity, they believe. That Modi shares this view becomes apparent in a conversation about the Hindu shrine of Rama at Ayodhya, now built on the site of a mosque that a Hindu mob destroyed in 1992.

The return of Shri Ram to his birthplace marked a historic moment of unity for the nation.”

– Narendra Modi

The site was disputed for more than a century; a Mughal ruler built the mosque on top of a structure that Hindus believe marked the place where Rama was born. The Supreme Court eventually resolved the dispute in favor of Hindus, and Modi himself led the dedication of the shrine in January after an 11-day fast.

He scoffs at any suggestion that India’s religious minorities, including 200 million Muslims, are mistreated. “These are usual tropes of some people who don’t bother to meet people outside their bubbles. Even India’s minorities don’t buy this narrative anymore,” Modi told Newsweek.

Getty Images

Many of India’s Muslims, Christians and other non-Hindu groups don’t see it that way. Asaduddin Owaisi, a member of Parliament, knows the BJP’s majoritarian policies are popular enough to win elections. He also sees them creating an atmosphere that enables attacks on Muslims, from physical violence to discrimination in food, dress and education. “Modi’s electoral victories are basically a mandate…for anti-Muslim policies,” Owaisi, president of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, one of India’s Muslim political parties, told Newsweek.

Other fault lines run through the economy. Official data show India’s unemployment at just under 4 percent. Many economists see those numbers as something of a mirage. “If you visit a notary in New Delhi, you will probably see four people around him, all supposedly employed. One to hold the pen, one to move the paper, one to place the seal and the fourth to make tea,” said Chakravorti, making a point about India’s massive problem with underemployment.

The unemployment rate for people with college degrees is nine times higher than that for those who cannot read or write, the International Labour Organization said in an April report. This dynamic creates a surge of overqualified applicants for government jobs. When a state police department posted job ads for manual office helpers, it was looking for candidates who had completed fifth grade. More than 33,000 people with college degrees applied. These trends have a disproportionate impact on Indian women, who have made remarkable progress in getting access to higher education and now make up more than 40 percent of all STEM graduates but just about a quarter of the STEM workforce. “Indian women are rising with clear aspirations,” said Debjani Ghosh, president of the National Association of Software and Service Companies.

Finding productive employment for an exploding workforce will be key to seizing India’s new economic opportunities and addressing the inequality that has plagued it for generations.

Despite these and other challenges, polls show Modi headed for a third consecutive term as prime minister, something no Indian leader has accomplished since 1962. Even in 1962 and with no serious national opposition, Jawaharlal Nehru, architect of modern India, won only a diminished majority. By contrast, Modi’s BJP looks set to increase its majority in the lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha, in a multistage election that ends in June with 960 million people eligible to vote. The main opposition Congress, dominated by Sonia Gandhi, the Italian-born widow of Nehru’s grandson, and fronted by her son Rahul Gandhi, appears headed for its worst-ever showing. Congress Party President Mallikarjun Kharge declined to comment for this article; other senior Congress leaders did not respond.

Modi himself, at 73, is more popular than the BJP. In regional elections outside the main Hindi-speaking heartland in northern and central India, national parties usually support their regional leaders, hoping to win over local voters in a country with more than 120 major languages. In the Modi era, the BJP has reversed that strategy and built its regional campaigns around him. In February, Morning Consult gave Modi a domestic approval rating of nearly 78 percent, making him the most popular global leader in its survey, with more than double the support of Joe Biden. Norwegian politician and peace negotiator Erik Solheim posted the survey on X, formerly Twitter, and asked, “Maybe it is time for Western media to give India and Modiji some positive coverage?”

Getty Images

Whatever the nature of the coverage, this election could well represent a turning point for India. For decades after independence in 1947, India was cast in Nehru’s image: secular, democratic, socialist, scientific and unapologetically non-aligned in the great power contests of the Cold War. A crushing victory at these elections would complete the process of casting India in Modi’s image: democratic, populist, technocratic, far more assertive on the world stage than Nehru ever imagined, and unapologetically Hindu and nationalist.

Turning the “Nehru Jacket” into the “Modi Vest” was just the beginning.

Danish Manzoor Bhat is Newsweek’s Asia editorial director.