Nicholas County is well-known in West Virginia for a few things. It’s known for Summersville Lake, the state’s largest body of water. And if you’re going to the lake to fish or boat, locals know to slow down for Route 19’s notorious speed trap. The other thing to know about Nicholas County is that they mine a lot of coal. Or used to, anyway.

Thirty-five years ago, state records show, about 1,500 miners dug some 9 million tons of coal a year from surface and deep mines in Nicholas County. By 2021, however, the number of mine jobs had dwindled to about 240 as many electric utilities switched to newly abundant natural gas and the nation’s use of coal plummeted.

That power switch hit especially hard in Appalachia, where rural communities—many already struggling economically even with the mining activity—lost coal jobs and tax revenue and had little else to take their place.

Photo-illustration by Newsweek/Getty

Nicholas County is one of 82 counties in Appalachia that the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) defines as in economic distress, meaning its unemployment, poverty and per capita income measures are among the nation’s worst.

Most of the region’s counties in distress are or were coal producers and, in addition to the lost jobs and revenue, many mining communities were left with the legacy costs from the industry’s environmental damage. Land and streams altered by surface mines can carry the risk of erosion, flooding and polluted runoff.

“It’s an area that’s trying to figure out what is the next chapter, and trying to figure out how can we transform things that have been mine-scarred into something that’s an asset again,” Jacob Hannah, CEO of Coalfield Development, told Newsweek. Coalfield Development is a West Virginia nonprofit that aims to help coal communities find a new economic footing through a combination of “gumption, grit and grace,” according to its mission statement.

The group partnered with renewable energy development company Savion to win an award from the U.S. Department of Energy for a project to bring clean energy to coal country. The project will turn two old surface mine sites in Nicholas County into a 250-megawatt solar farm while training former coal industry workers in the area for new trades in renewable energy.

“That’s not really been done before, to really marry solar with coal legacy infrastructure like this would be,” Hannah said.

Some former surface mines in the region have been converted to other uses ranging from golf courses to shopping malls, but many remain unused eyesores and public hazards. The barren bedrock is often unsuitable for agriculture, and several attempts to build on old strip mines in the region have been thwarted when the land settled and shifted, threatening or damaging structures on the surface.

But the old mine sites have some advantages for solar energy. Their open terrain allows panels sun exposure, access roads are in place, and a former mine’s electricity supply lines could be repurposed to connect the solar power to the grid.

Courtesy of Coalfield Development/JJN Multimedia

To make use of those assets, the Nicholas County solar project will pair private funding with $129 million from the DOE’s Clean Energy Demonstration Program, one of three projects across Appalachian coal country that were collectively awarded a total of $300 million in March. A project in eastern Kentucky received $81 million and another in central Pennsylvania received $90 million.

The companies and partner organizations involved aim to convert old coal mines into new sources of clean energy and to leverage that investment to help the surrounding communities make the transition into an economy beyond coal.

“It’s a commitment to the communities in and around Nicholas County that you can build this thing, but you can also have it truly transform local lives,” Hannah said.

From Coal Mine to Water Power

The DOE award in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, will also support a solar installation. It’s expected to be the state’s largest solar site when completed, a 402-megawatt project on some 2,700 acres of repurposed mine lands. As with the West Virginia project, the Clearfield County project also dedicates funding to local job training.

The third clean-energy project in the region, however, will take a different approach to help solve one of renewable power’s shortcomings by installing energy storage on an old coal mine in Bell County, Kentucky.

Courtesy of Rye Development

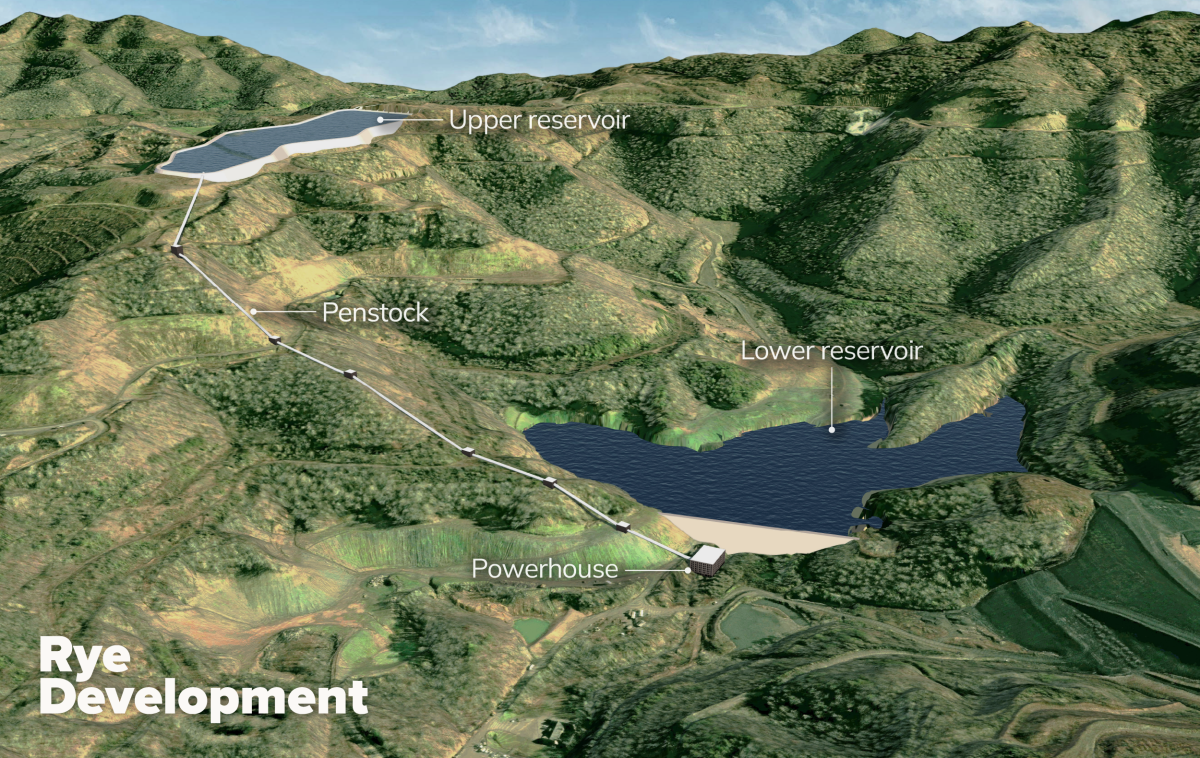

There, hydroelectric construction company Rye Development plans the Lewis Ridge Project, a pumped hydro storage facility that uses water and gravity to create a sort of battery.

“What you’re doing is storing energy in the form of water,” Rye Development CEO Paul Jacob told Newsweek.

The company plans two reservoirs on the hilly old surface mine property, one several hundred feet higher uphill from the other, and connected by pipes running up the hillside.

“When there’s excess energy in the system, you’re taking water and you’re pumping it uphill,” Jacob explained, akin to charging a battery. “Then when you need that energy, you release it, and it flows downhill.”

On the way down, the water turns a turbine, generating 287 megawatts of electricity, enough to power about 67,000 homes for up to eight hours. Rye is also exploring the possibility of floating solar panels atop the reservoirs to further boost power production.

The pumped hydro storage idea isn’t new—Jacob said the first such project in the country dates back to the 1920s—but it takes on a new spin in connection with renewable energy.

Solar and wind power are only available when the sun shines and wind blows, and that intermittency can be a challenge for the power grid’s managers who need to match electricity supply with demand.

Pumped hydro is a way to store clean power and help even out the peaks and valleys of power demand. That reduces the need for fossil fuel “peaker plants” typically used to meet sudden demand spikes and can also help make the grid more resilient to potential disruptions.

Grid-scale batteries are a rapidly growing form of energy storage for wind and solar, but Jacob pointed out one advantage of pumped hydro. Unlike electrochemical batteries, which have a limited life of charging cycles, water has no such limit.

“That first project that was built in the 1920s is still operating today,” he said.

Courtesy of Rye Development

Rye Development is a partnership with the investment firm Climate Adaptive Infrastructure and EDF Inc., a subsidiary of the EDF Group, a global energy company based in France that operates hydropower. EDF is on Newsweek‘s most recent ranking of the World’s Most Trustworthy Companies, released in 2023, where it ranks 49th among 55 companies in the energy and utilities sector.

The engineering and construction of pumped hydro storage is labor and capital intensive and time consuming compared to the installation of grid-scale batteries for renewables. Jacob estimates the construction will begin in 2027 and take four years to complete.

However, that also makes the project a substantial economic boost for Bell County and the surrounding area—a $1 billion investment that’s expected to create 1,500 jobs during construction. Jacob said the area workforce has many of the skills his company will need.

“Constructing a project like this—it’s about moving great huge quantities of earth to get it built,” he said. “It’s all of the things that are currently done in the process of mining coal.”

Mining Communities Look for Long-Term Fixes

Bell County sorely needs the sort of economic shot in the arm that the Lewis Ridge Project could deliver. Tucked in the state’s southeastern corner along the border with Tennessee, Bell is another of the counties the ARC designated as economically distressed, as are many of the surrounding ones in eastern Kentucky.

Bell County is part of the state’s 5th Congressional District, which is the second-poorest district in the country.

“Rural counties in the greater Ohio Valley region and in much of the Midwest as well have been having a really tough go of it economically,” Sean O’Leary, a senior researcher at the nonprofit regional think tank Ohio River Valley Institute, told Newsweek. “Many of them have experienced both job and population losses, while the rest of the country, more urban and metropolitan America, was growing.”

O’Leary said the clean-energy projects will be a very positive development for the region but not a panacea for its economic problems. He hopes communities take a lesson from past over-reliance on energy production facilities, which typically do not generate as many long-term jobs as other industrial activities.

“For too long in our region, we’ve looked to coal and, more recently, natural gas as being engines for economic prosperity and recovery, and they’re not,” he said.

The clean-energy projects supported by the DOE come with some impressive job creation estimates, but most of those jobs come in the short period of constructing the projects. In Nicholas County, West Virginia, for example, the DOE estimates 400 construction jobs to build the solar project but just four long-term operations jobs.

“Those communities should do as much as they can to make sure that a healthy portion of the revenue that those facilities generate actually does land in the local economy,” O’Leary said.

The clean-energy projects are designed to maximize the local economic impact. In Nicholas County, the solar project is expected to pay $18.5 million in property taxes over the project’s lifetime, which would help fill the gap left by revenue that was lost when the coal mines closed.

Courtesy of Coalfield Development/JJN Multimedia

In addition, Hannah’s group will join with other organizations and a local community college to create a national Coal Transition Workforce Center to help people find new jobs in clean energy construction and development.

“There’s over 800,000 acres of abandoned mine land in Appalachia,” Hannah said, and part of the goal for the Nicholas County project is to provide a model for other struggling coal communities.

Now that the nation is turning to new forms of energy for the future, he said, it’s important to take care of those that powered us in the past: “To produce energy and do that in a way that honors the history and the legacy of the region, while still giving opportunities for new economic drivers.”