It was 1963, the “Year Everything Happened,” according to one documentarian. The Beatles released their first album. Hundreds of thousands gathered on the national mall to hear Rev. Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. President Kennedy was assassinated.

It was no less momentous for me. As an officer in the Foreign Service, I was given my first overseas assignment. To Damascus, Syria I went.

All these years later, I can still remember the chaos that day I arrived. A member of the American embassy staff was showing me around the city. We’d just stopped on a bluff overlooking the city when everything suddenly changed.

“Let’s get out of here,” he shouted, jumping into his car and pulling me with him. An attempted coup was underway, and the Syrian government had declared an immediate curfew. Anyone in the streets could be shot. He’d heard this over the car radio.

That night, I watched as military jet fighters crossed the skies and military tanks overtook the streets outside my family’s apartment.

Only a few months later, I found myself in the midst of another would-be revolution while visiting an ancient market.

Out of nowhere, shop owners began to slam shut their metal shutters, and the streets emptied. Before I could discern what was happening, police arrived in trucks armed with water cannons and truncheons. They were there to suppress the uprising, which resulted in several cities being bombed into debris.

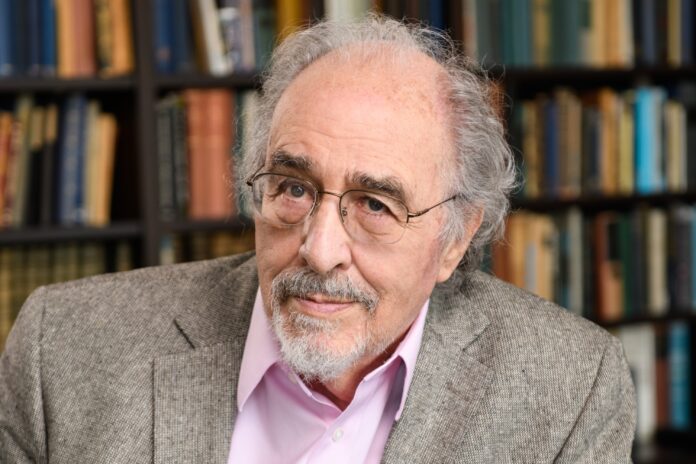

Otho Eskin

These events have stayed with me over the years. But it’s another memory from Damascus that truly haunts me. It has even made its way onto the page, as I’ve turned, in my eighties, to fiction writing.

It involves an American who was clinging to life following a drug overdose.

One of my responsibilities as an embassy officer was to look after American citizens who got themselves into trouble. One day, the chief of police called me to a local prison, which had actually been built as a Roman fortress. I was not prepared for what I saw there.

Before me, in the shadows, was a person in a terrible psychological state. He was conscious but speaking nonsense. He was clearly under the influence of some drug. He was just a kid—it turned out, an undergraduate who’d gone on a stupid spree. There was an American hospital in Beirut, Lebanon, that kept psychiatrists on staff. So I arranged for one of these specialists to come to Damascus to examine him.

Upon seeing the patient and the dungeon—and that’s really what it was—the psychiatrist expressed fear for the kid’s welfare. He said that even after the drug wore off, the kid might never recover from the experience of being detained there without proper medical attention.

I worked with the psychiatrist to persuade Syrian authorities to permit me to drive the kid across the border to Beirut in Lebanon. They agreed on the condition that we take an embassy car with diplomatic plates. I think they were relieved—why would they want this crazy American on their hands?

When the time came to leave, the kid began to act even more erratically. I wondered if it was safe for me to transport him. What if he became violent? I decided to procure a straightjacket, as well as to recruit one of the young Marines stationed at the embassy.

If need be, this muscled guy and I could manipulate the kid into the jacket. It wouldn’t be easy, but we could do it.

It struck me how similar in age the two of my companions were. In another life, they might have been chums. But here they appeared as night and day: the one, looking dignified in his uniform, and the other, frantic and wild-eyed. I wonder if the same thought crossed the Marine’s mind. He was clearly perturbed by the situation, stealing glances at our charge and furrowing his brow. He, too, had great concern for this troubled soul.

We delivered the kid to the hospital in Lebanon. An American psychiatrist evaluated him and then put him on a plane to New York, accompanied by a nurse armed with a serious tranquilizer.

What happened next to this poor boy? Over the years, I’ve often asked myself this. Did he have loved ones waiting for him at home? Did he receive good medical care? Did he land on his feet and finish college? Did he marry and start a family? Or was he scarred by what happened in that prison following his stupid spree? Did he become an addict for life?

I think of him every time I read about a young person destroyed by drugs—these days, increasingly by opioids. I fear he might not have survived his bad decision had fentanyl been on the streets. It is more powerful than OxyContin and has killed millions of Americans.

Perturbed by this memory, and outraged by the apparent complicity of the pharmaceutical industry, I decided to write my third thriller novel about the opioid crisis, taking a homicide detective on his most perilous mission yet, as a drug more dangerous than fentanyl hits the streets.

I might have focused this story on a victim resembling the kid I met all those years ago. I certainly remember him well enough. But I chose to center on the villains, who all too seldom find themselves in dungeons—instead living in splendor as the bodies pile up and people in the prime of life are devastated by addiction.

I wanted to pull back the curtain on the ones who have art galleries named in their honor, using their charitable donations to create a veneer of generosity.

Today, as in 1963, society is full of injustice. Sometimes the headlines tempt me to despair. But like my younger self who put his family on a plane and traveled to a faraway place, I believe we can build a better world.

Fiction allows me to imagine the bad guys getting their due—and the good ones winning the day. It allows me to nod along when an old Beatles song comes on the radio and Paul McCartney croons, “It’s getting better all the time.” It allows me to hope that if my own children or grandchildren were ever to lose their way, they would encounter fellow travelers who would try their best to make things right.

I’m now 89, and the stranger that I met in the 1960s still haunts me.

Otho Eskin is a playwright and the author of the Marko Zorn thriller series, two books of which were named Amazon Editors’ Picks. Prior to taking up his pen, he practiced law and served in the U.S. Army and Foreign Service.

All views expressed are the author’s own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at [email protected].

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.