I started to sell crack to keep a few dollars in my pocket to make up the difference for what my mom couldn’t do at the time. It wasn’t like I envisioned myself as some rising kingpin. I never saw myself running a block; I just wanted to make some bread.

There was a dude on the block that we’ll call OG Juice. Juice was a professional criminal. He was street savvy and had a lot of game. For some reason, Juice embraced me and looked out for me.

Eventually I discovered that he sold my mama dope, but I didn’t know at the time. Anytime he and I would do business, it would be when my mother wasn’t there. Juice knew I didn’t cook dope so he would sell me what he had already bagged up, sometimes twenty to thirty rocks at a time. He always gave me a slight discount so that I could make a profit.

I sold on the move, up and down blocks around my neighborhood, either walking or on a bike. I didn’t have a gun nor did I have a designated block. Movement and being aware of my surroundings at all times were my means of staying safe and out of the way.

I learned to watch and identify every car that passed by, and I kept a mental log just in case a car doubled back. This could be an undercover narcotics officer or a jacker, somebody looking to rob you for your dope.

Harper Horizon

I would rotate my bundle between my pocket and my mouth. If I kept rocks in my mouth for too long, my mouth would go numb. If the police pulled up, I could just swallow the dope—though I never thought I would actually have to do that.

If I saw a knock—our name for a crack addict—coming my way, we would make eye contact; they would give a nod, as if to ask, “Do you have it?” I would give myself a few seconds to read the play. Do I recognize this person? Do they look hot? Should I serve them? If I calculated wrong, I was going to prison for a very long time.

They would whisper the desired amount they wanted, I would spit it out of my mouth, and we would exchange money for drugs. I would take the money, look over my shoulder, and keep it moving. I didn’t roll with a crew and I didn’t really have a strategy selling drugs, so I never felt entirely comfortable—with good reason.

One night I was in front of my apartment building on Fifty-Fifth and Market and a dude we’ll call Big Dub pulled up. Dub sold dope in my neighborhood, but I didn’t realize that he considered my block part of his territory.

I usually tried to stay on the move, but on this night for some reason I decided to post up in one place: in front of the building where I lived.

“Hey, blood, what’s up?” Dub said.

“What’s up?” I answered.

“What you out here doing?” he asked. “

Nothing, bruh. I’m just posted up.”

“I hope you not out here selling dope or nothin’, bro. You know this is my spot, right?”

“No, I don’t know what you talking about, bro. Like I said, I’m just postin’. I ain’t selling no dope.”

In fact, I had a pocketful of dope. But what I didn’t have was a strap. If he wanted to get spunky, I wasn’t prepared. He pulled off without saying another word. I let out a deep exhale. I don’t know if he saw through me and knew I was lying to him.

From that encounter, I knew that he was going to keep watching me. I wasn’t really consistent with the dope selling. He might see me moving around the neighborhood, but it was probably hard for him to put his finger on what I was doing.

A couple months later, the streets caught up with Dub—he got shot in the head right in front of his house on Market Street, two blocks from my house.

In retrospect, moments like that encounter with Big Dub allowed me to see all the times that God had mercy on me. He kept me safe despite the way I was living at that time. Deep down I knew I wasn’t fully committed to the street life.

It’s like when I talk to a boxer about the boxing life, I want to know, “Are you in it for the money? Are you in it for the fame? Or do you just like the idea of what comes with being a champion?”

I can read a fighter with ease, gauge their level of commitment. I think on the streets some dudes could peep that about me. I’m sure they knew I wasn’t fully living it. It would have been too easy for me to lose my life right there on the block, just like Dub did.

The dudes I was running with knew I was a boxer; they heard about my accomplishments. I had a reputation. But they didn’t know how deep I was involved in the sport or how I was squandering it all. In my mind, I was no longer that guy—the boxing stuff was in the rearview mirror.

They knew me as young Dre, or Madeline’s son. They didn’t know me as a fighter. My mom would always brag about me being a boxer, but I could tell they didn’t really get it. Probably because I had one foot in boxing and one foot in the streets.

Nobody on the streets was saying, “Yo, you the next one, bro. We got to protect you.” That’s the kind of thing you see with a young basketball or football phenom.

In my case, maybe if I was living the life of an athlete, if they saw me going to the gym, running regularly, they might have taken that position. But what they saw was a young kid on the street corner, hustling, selling drugs and making bad decisions.

When my mother started slipping again, we would get into these blowups. I would accuse her and she would constantly deny it.

“I’m only smoking a little weed—what’s wrong with that?” she said.

“Mama, you ain’t just smoking weed. I know that look.”

“Well, you can think what you want to think!”

“Naw, Mom, I know what I’m looking at.”

Another time I found broken pieces of pipe in her room. I brought the evidence to her, but still she denied.

“Oh, Shanae was over here—that’s hers.”

“Mom, what are you talkin’ about? I ain’t no fool! I’ve been through this before. I’m looking at how you’re movin’. I’m looking at this house.”

“All you want to do is blame me every time you think I’m back using!”

By now, I had developed a keen eye for spotting a drug user—an expertise I never wanted. The brutal thing about crack is that it supersedes everything else in your life—your dignity, your family, and truth. Everything gets drowned out by the desire to want to get high.

With Mom, it was especially painful because she had beaten this addiction multiple times before; God had answered her prayers and delivered her. She would be fine. But that was the pattern of my life—Mom is good, then she would relapse; Dad is good, Dad would relapse. Over and over.

I wasn’t a kid anymore. I was older now and had years of experience studying both of my parents. I wasn’t going to just fall apart. My heart had hardened; though it would still hurt, I wouldn’t show it. I became numb. I remained in this state by abusing drugs and alcohol and distancing myself.

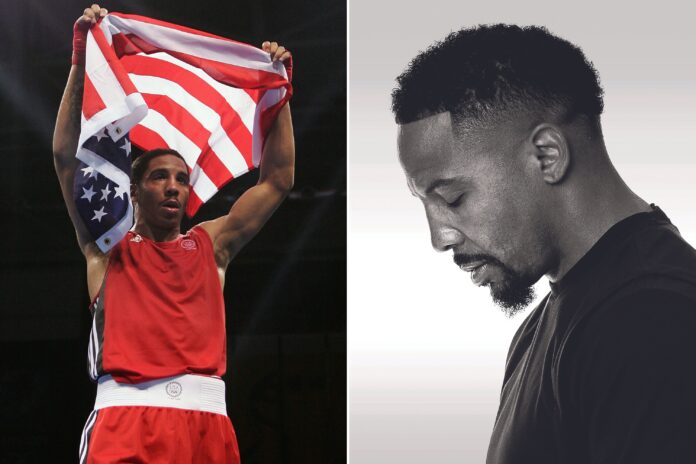

Al Bello/Getty Images/Harper Horizon

Virg, my boxing trainer, wasn’t letting my drift go unaddressed. He was getting at me about the way I was living. Virg lived his life like he was playing chess. He would see and hear things about me but wouldn’t reveal what he knew until he was ready to drop the hammer and confront me.

But I was pushing back, not receiving what he was trying to give me. I was moving away from him. I was able to clean myself up for certain periods to get ready for the big tournaments. Virg would track me down and get me to focus for a four- or five-week period.

“Come on, we need this, Dre. Gotta get focused.”

I would be able to stay away from the streets and get myself together long enough to go win another national title. I was the number one ranked amateur in the country, but I was still missing a lot of tournaments too.

When you’re on the amateur boxing circuit, you’re fighting all throughout the year. A few times I did enough to qualify for the Nationals but then didn’t show up. A week or a few days before it was time to leave, I would come up with an excuse.

“Aw, man, Virg, uh, my back hurts. I don’t know if I can go.”

Another time I said it was my knee, or I would just disappear altogether and leave him hanging. Looking back on this period is shameful, but it goes to show what kind of person you can become if you allow yourself to drift too far.

My lifestyle was showing up in the boxing gym. There were times when I would be in the streets all night, drinking and smoking weed, and Virg would call me and expect me to be in the gym the next morning, ready to spar. I would show up, knowing that I wasn’t at my best.

Everybody in the gym still looked at me like an Olympic hopeful, but I didn’t feel like one. I would be strong for two or three rounds and then I would start to feel nauseous. The poison I had consumed the night before was coming up whether I wanted it to or not.

I would run to the corner and throw up in a bucket. Virg could smell the alcohol on my breath and would give me this deep look of disappointment and shake his head. I would finish the sparring session by coasting to the final bell, uninterested in exerting too much effort for fear I would throw up again.

Virg would take off my sparring equipment, barely saying anything more than, “Son, you’ve got to get yourself together. You don’t have much time left.”

I blew off the National Golden Gloves in 2002 in Las Vegas. James Prince, who is a boxing manager and the CEO of Rap-A-Lot Records, flew to Vegas to see me fight. He was disappointed that I didn’t show up, but Prince didn’t leave it there.

To this day, I still don’t know how Virg tracked me down and got me on the phone. I was at a trap house tucked away. Prince wanted to know why I wasn’t at the Nationals.

I began to tell Prince everything I had going on in my life and I expected him to back away, but Prince didn’t hesitate when he said, “We’re gonna take care of all those misdemeanor problems. We just need to get you back in the ring.”

He wasn’t talking about a police record. He was referencing the issues that I was dealing with. Prince and I wouldn’t speak again for several months, but that conversation left an impression on me. He was the first manager to go out of his way and run me down to express that he wanted to do business. I respected that.

Virg was still in my ear constantly, trying to get me to see the light. He would appeal to me on a spiritual level, telling me the devil wanted to take me out but God loved me. He talked to me about the generational curses of drug use that existed in my family. He would tell me that I was giving in to the same forces that my mother and father battled for much of their lives. And he also took it to the streets.

“Brother, let me tell you something,” he said. “You out here fakin’.”

I was angry when I heard that. “What you mean, fakin’?! Ain’t nothin’ fake about me!”

“Look, you out there playing and roaming around like you’re established in the streets. You ain’t making no moves in the streets. You ain’t no kingpin. You ain’t running no block. You just running around here with a bunch of dudes getting high. That’s what you’re doing. You ain’t really about that life.”

“Man, you trippin’, Virg,” I responded.

“Let me tell you something. If you ain’t ready to sell your soul to the devil right now and be willing to kill somebody, if you ain’t ready to be killed, you fakin’ out here in these streets.”

Even though what he said angered me, it also shook me up. I had never really thought about the level of treachery that it takes to survive in the streets until that moment. But he was right. I played it off in front of him, but when I got away from him I sat with that for a long time.

The reality was I wasn’t trying to kill nobody, and I definitely wasn’t trying to be killed. Again, it was like boxing—you can’t go into a big fight without embracing and acknowledging the fact that you might get knocked out.

You’re telling yourself it ain’t gonna happen—you’re gonna win this fight. But you’re ready for the worst-case scenario. It’s the same in the streets. That’s the point that Virg was trying to make, because that’s the type of individuals you’re dealing with.

Still, I was young and rebellious. Virg’s words alone weren’t going to do it. But in the midst of my rebellion, I had two experiences that finally managed to penetrate my hard head and begin to break me down.

I was standing in front of a liquor store on Fifty-Sixth and Market as I sold a couple rocks to this lady. As soon as I finished the transaction, I had a clear thought pop into my head, almost like a voice talking to me: How are you going to ask me to take away your mother’s addiction but you’re serving somebody else’s mama crack? You’re poisoning your community, but you want me to deliver your mother?

I was stunned. I felt shame creeping in. I knew it was God showing me how I was acting like a straight hypocrite. My mother was a block away with an active crack addiction that I was desperate to see shut down, yet I was enabling somebody else’s mom in her addiction.

This moment revealed to me how desensitized I had become, but it also showed that I wasn’t too far gone and my conscience was still active.

The lady I served drugs to was wearing a long overcoat and a beanie on her head, and she didn’t have any teeth. Clearly, she was deep in the throes of her addiction. I felt convicted for my selfishness, being so blinded by the money and the lure of the streets that I would have the audacity to pray for the taste to be taken from my mother’s mouth as I fed the taste to someone else’s.

It was God chipping away at me, delivering another timely warning. Often, warning comes before destruction. I felt the warnings, but I still wasn’t ready to surrender my life to God.

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

I was still out there, but now I found myself being a little more careful in my movements, keeping my eyes peeled for dudes like Big Dub and for the police. I was aware of the California mandatory minimums at that time for selling drugs. Usually ten or fifteen rocks even with no record would get you at least three years in state prison. I just missed that bus ride to San Quentin.

I got hit with another warning a few months later, two blocks from where I lived. I was riding my bike slowly, looking for knocks, holding about twelve rocks in my mouth. When I turned a corner on the bike, a cop car pulled up behind me. The car shined its floodlights at me. I felt my stomach drop.

“Hey, you! Stop!”

The voice was amplified over the car’s loudspeaker. I stopped my bike. My mouth was filled with a bunch of crack cocaine. I had to make a quick decision. Swallow the rocks or go to prison. I started to swallow them one by one as I set my bike down slowly, trying to buy a little time.

The rocks were double bagged, so I felt like I was safe enough to swallow a few. I slowly turned around as I could hear the cop approaching me. I swallowed a few more rocks, enough to talk without sounding crazy.

“What’s the problem?” I said, carefully controlling my voice.

“Where you going?” the cop said.

“Sir, I’m just riding my bike. I’m not bothering anybody. I live around the corner.”

“Yeah, but I see you riding around looking suspicious,” he said.

I was trying to talk without the rest of the rocks falling out of my mouth. It was too late to try to swallow any more of them. Even as I was talking, I was feeling a growing sense of panic about the ones I already swallowed—while fighting the fear that I could be arrested for possession.

He moved closer to me, shining the flashlight in my face.

“You ain’t doin’ nothin’, huh?” the cop asked me, watching my face closely.

“Man, I’m just heading home.”

Trying to back him off of me, I started to get bolder. I added, “You want to follow me to my house? I live around the corner—what’s the problem?”

“I’m just checking, man. Calm down,” he said.

He studied me for another minute or so, then turned around and headed back to his car. As I climbed on the bike, I felt around in my mouth. I had swallowed all but two of them. I spit those two out and put them in my pocket.

I just swallowed ten crack rocks! The panic rose in my body as I pumped my legs and raced home as fast as I could.

“Mama! Mama!” I screamed when I busted through our front door. “I just swallowed ten rocks!”

“What you mean?” she said when she saw me.

“I was out there trying to make some money . . . This cop got behind me!”

I knew that I had to get them out of my system as quickly as possible. If the acid in your stomach made them bust open before you could use the bathroom, you could overdose and die. I thanked God that OG Juice had done what he was supposed to do and double-bagged the rocks.

But even with the double bags, I knew I was in a life-or-death situation. I ran to the liquor store and bought chocolate Ex-Lax. I quickly downed three bars of the Ex-Lax before I even got back home. I sat on the toilet immediately but nothing happened—obviously the Ex-Lax wasn’t going to work that fast.

I was thoroughly spooked. Logic had flown out the window. At any moment I could have a heart attack or overdose. I just had to wait it out, terrified the whole time, thinking wild thoughts.

“Boy, I can’t believe you out there selling dope!” my mother said. “You know, you can get yourself killed out there in them streets.”

“I know, Mom. But how you gonna tell me what I need to be doing when you out there doing drugs?”

That wasn’t the first time we had had this argument. We went back and forth for a while. Eventually I moved away from her and started talking to God.

“Lord, please don’t let me die like this.”

I went to the toilet again. The Ex-Lax was starting to do its job. Real street hustlers go in the toilet to fetch out their dope, clean it off, and hit the block again to go sell it.

I wasn’t thinking about that dope nor the money I had just lost either. The warnings were piling up and I didn’t know how many I had left.

My life was spiraling out of control, but when that dope got flushed, my drug-selling days got flushed down the toilet right along with it.

Andre Ward is married to his high school sweetheart, Tiffiney. Together with their five children, they live in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is a retired world champion and Hall of Fame boxer, as well as a licensed minister and youth pastor at his church, The Well Christian Community in Livermore, California.

This is an extract from Andre Ward’s memoir Killing the Image, released with Harper Horizon on November 14, 2023, and available for purchase in hardcover, ebook, and audiobook at leading bookstores and online retailers.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at [email protected].

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.