Researchers have revealed a previously unknown species of “giant sea lizard” with a fearsome set of “dagger-like” teeth that lived during the age of the dinosaurs.

The new species, described in a study published in the journal Cretaceous Research, is a type of mosasaur—a group of large extinct marine reptiles that ruled the oceans in the latter stages of the Late Cretaceous period (around 100 million to 66 million years ago).

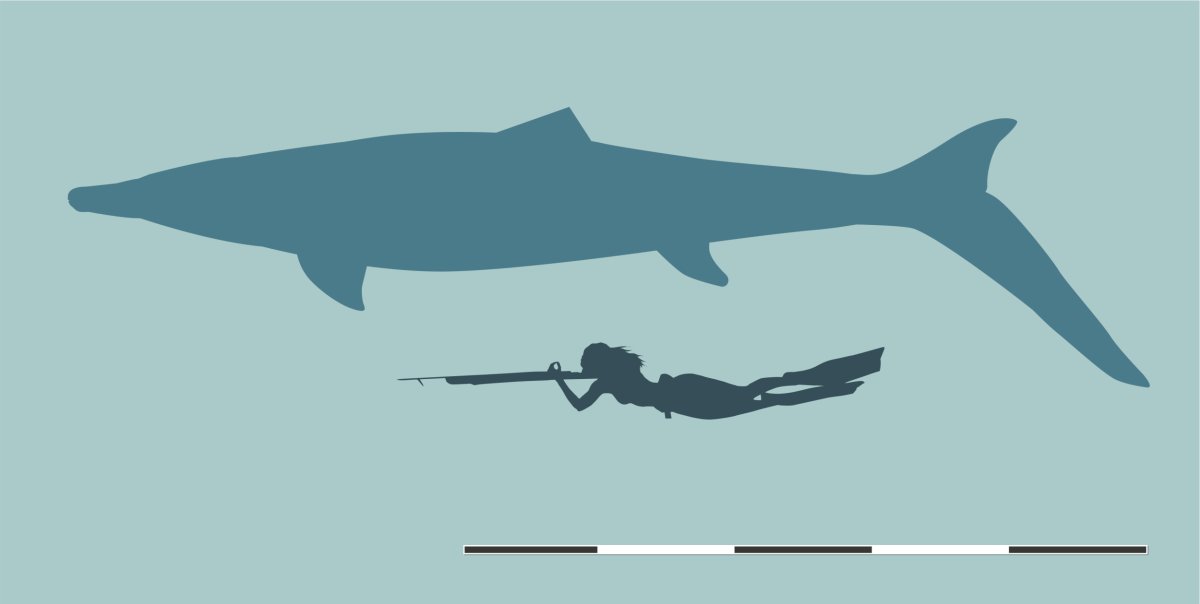

These prehistoric sea creatures had long, slender bodies, similar to those of modern-day monitor lizards, albeit streamlined for swimming, featuring webbed feet and toes, as well as broad, powerful tails. Capable of reaching high speeds, they were skilled hunters, with their jaws containing dozens of sharp teeth. The largest mosasaurs may have reached lengths of more than 40 feet.

Mosasaurs disappeared—along with the dinosaurs (apart from birds)—as a result of the mass extinction event that occurred roughly 66 million years ago, which is thought to have been caused by a massive asteroid impact.

Nicholas Longrich/Longrich et al., Cretaceous Research 2024

“Mosasaurs are giant sea lizards,” Nick Longrich, a paleontologist with the University of Bath in the United Kingdom, who led the study, told Newsweek. “They were highly specialized for marine environments, and fully aquatic. Their legs were transformed into whale-like flippers, the tail had a shark-like tail fin [and] they gave live birth like whales.”

“They’re somewhat equivalent to whales and dolphins in terms of the niches they occupied, but being lizards, different as well,” he said. “They didn’t have sonar but probably had forked tongues to scent prey underwater. Like snakes and Komodo dragons, their lower jaws could expand to eat huge prey.”

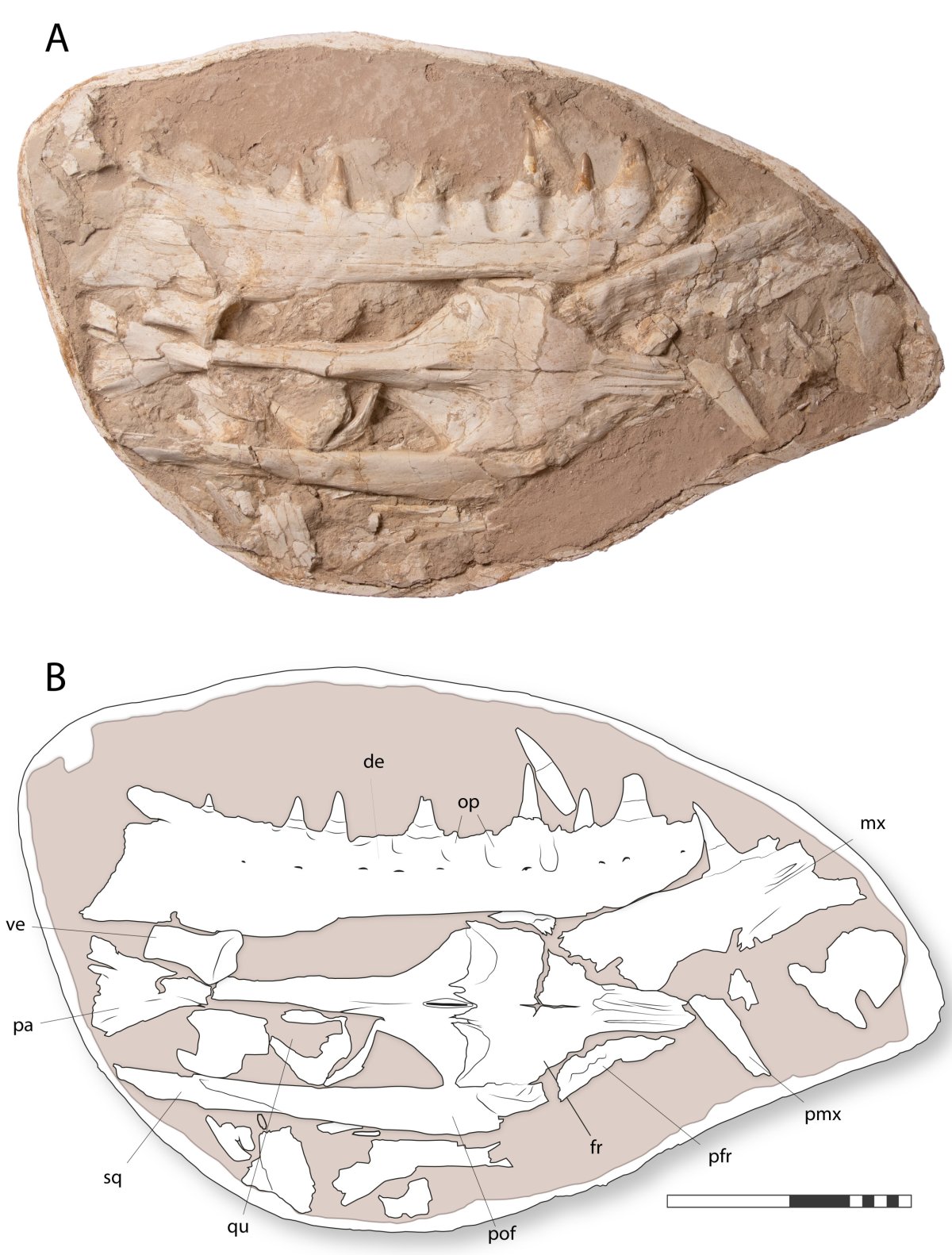

The newly identified mosasaur, named Khinjaria acutus, was described based on an incomplete set of fossilized bones dug up in the phosphate mines of Sidi Chennane, in Khouribga Province, Morocco. The collected bones include most of a skull—a lower jaw, an upper jaw, most of the braincase and teeth—as a well as a handful of vertebra.

The fossils date back to the Maastrichtian age—the final stage of the Late Cretaceous—which lasted from around 72 million to 66 million years ago.

“These fossils might be around 67-69 million years old, if I had to guess,” Longrich said. “They’re a little bit older than most of the other mosasaurs, which date to 66-67 million years ago, but not a lot older. We’re still trying to figure this part out.”

Extrapolating from closely related mosasaurs, Khinjaria probably measured around 23-25 feet in length and likely would have been able to open its jaws wide enough to swallow a human whole, according to Longrich.

Like other mosasaurs, it was probably a “top predator” during its day, although perhaps not at the very top of the food chain, Longrich said. Among the animal’s most notable features are a series of large, “dagger-like” teeth at the front of its powerful jaws.

“It was larger than a great white, but the teeth are more like a mako shark’s teeth. Makos feed on things like large fish and squid, occasionally sharks and marine mammals. It probably had a fairly similar diet, but, being a lot larger than a mako, took correspondingly bigger fish,” Longrich said.

Longrich et al., Cretaceous Research 2024

Khinjaria differs from other known mosasaurs in having a very short face, while the back of the skull is very long, leading the study authors to describe the specimen as “bizarre” in the paper.

“Mosasaurs aren’t exactly pretty creatures, but some of them are uglier than others, and Khinjaria acuta may well take first in the ugly contest,” Longrich wrote in a blog post on his website. “Its eyes are small and beady, the face is short and massive, the back of the skull is weirdly stretched out. The jaws were powerful, with the teeth in the front of the jaws being long, straight, and flattened side to side, like a set of daggers, giving it a wicked smile. This mosasasur is positively demonic.”

In fact, the animal’s name refers to its teeth—the word “khinjar” being an Arabic word for “dagger” and “acuta” being Latin for “sharp”.

Longrich et al., Cretaceous Research 2024

The marine environment that this creature lived in was characterized by an “extraordinary abundance” of plankton and small fish eating them, which fed a huge range of large predators.

“It’s an astonishingly diverse marine ecosystem—huge numbers of fish, sharks, sea turtles, long-necked plesiosaurs and of course the mosasaurs,” Longrich said. “We are seeing extraordinarily high predator diversity in the latest Cretaceous of Morocco.

“Partly that’s interesting because it says the marine ecosystems were thriving just before the asteroid struck wiped out the marine reptiles and dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous. Partly it suggests these ecosystems are structured in a fundamentally different way than modern ecosystems. Whether that’s because the climate and food items were different, or perhaps mosasaurs were able to exploit these ecosystems in a very different way, I’m not sure.”

The ecosystem was home to a surprisingly high number of mosasaurs among the various top predators.

“I think the really surprising thing is just how diverse the mosasaurs were,” Longrich said. “Whether there’s something unusual about this environment, or whether that’s caused by something inherent to the mosasaurs themselves, I don’t think we really know.”

Do you have an animal or nature story to share with Newsweek? Do you have a question about paleontology? Let us know via [email protected].

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.