The secrets of how Earth and other planets are formed may have been revealed after observations of a far-distant solar system.

Astronomers have found water vapor in high concentrations in the disc of rock orbiting a star in the early days of its solar system, from which planets will eventually form, according to a new paper in the journal Nature Astronomy.

This implies that Earth may have formed thanks to nearby water during its birth from a similar planetary disc of debris, over 4 billion years ago.

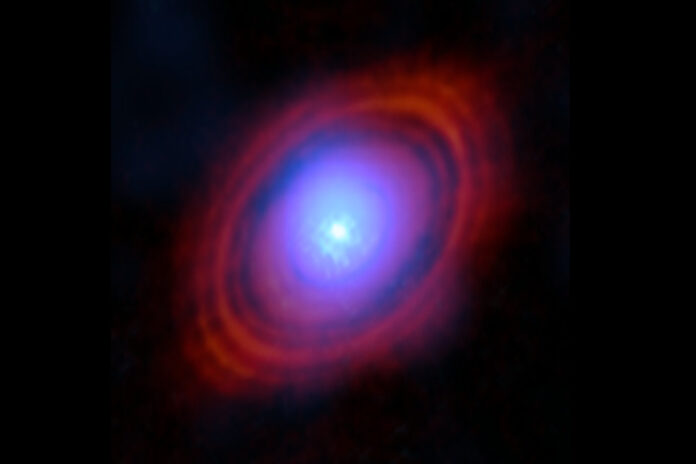

ALMA ESO/NAOJ/NRAO/S. Facchini et al.

“I had never imagined that we could capture an image of oceans of water vapor in the same region where a planet is likely forming,” study co-author Stefano Facchini, an astronomer at the University of Milan, Italy, said in a statement.

The paper reveals that there is about three times the amount of water in all the oceans on Earth in the disc around the star, which is named HL Tauri, and is situated about 450 light years away from the Earth. This marks the first time that the distribution of water in a stable, cool disc around a star has been mapped.

“It is truly remarkable that we can not only detect but also capture detailed images and spatially resolve water vapor at a distance of 450 light-years from us,” co-author Leonardo Testi, an astronomer at the University of Bologna, Italy, said in the statement.

Planets are formed through a process called accretion, which occurs within protoplanetary disks around young stars. When a cloud of gas and dust collapses under its own gravity, it forms a rotating disk around a central young star. Tiny dust grains within the disk collide and stick together, forming larger particles. This process continues, leading to the formation of pebbles and eventually city-sized planetesimals. As these planetesimals collide and accrete more material, they grow larger in size. Gravitational forces start to play a significant role in this phase, causing larger objects to attract smaller ones, leading to the formation of larger bodies known as protoplanets. These protoplanets continue to accrete material from the surrounding disk until they become fully-fledged planets.

This discovery was made using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which allowed for observation of the distribution of water around different locations in the disc. They found that a large amount of water was found in a place where they had previously found a gap in the disc. These gaps are usually formed as planets form, gathering up gas and dust as a planet snowballs into existence, which suggested that water vapor may also be taken into the planet as it formed.

“Our recent images reveal a substantial quantity of water vapor at a range of distances from the star that include a gap where a planet could potentially be forming at the present time,” says Facchini. “Our results show how the presence of water may influence the development of a planetary system, just like it did some 4.5 billion years ago in our own solar system.”

ESO/JOSÉ FRANCISCO SALGADO JOSEFRANCISCO.ORG

The astronomers suggest in the paper that water may freeze onto dust particles in the planetary disc, sticking the chunks together more effectively and seeding planet formation.

“It is truly exciting to directly witness, in a picture, water molecules being released from icy dust particles,” Elizabeth Humphreys, an astronomer at ESO who also participated in the study, said in the statement.

The ALMA telescope is especially suited for this kind of discovery as it is situated in the Chilean Atacama Desert at an elevation of over 16,000 feet.

“To date, ALMA is the only facility able to spatially resolve water in a cool planet-forming disc,” co-author Wouter Vlemmings, a professor at the Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, said in the statement.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about planets? Let us know via [email protected].

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.