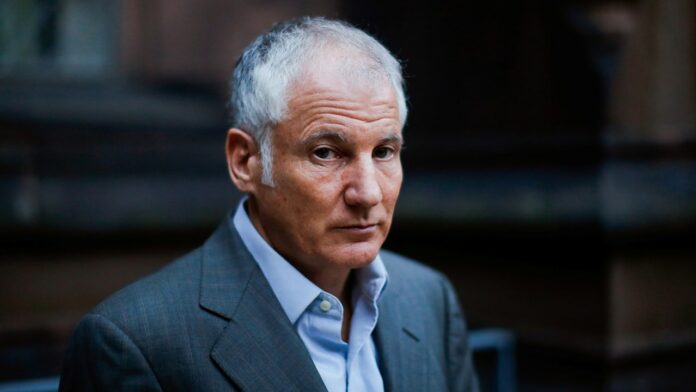

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, The New Yorker has been publishing on-the-ground reporting from our correspondents Luke Mogelson, Masha Gessen, and Joshua Yaffa, as well as commentary and reporting from Washington to Warsaw to the Baltic states. Throughout the conflict, I’ve been in touch with Stephen Kotkin, a professor of Russian history who taught at Princeton for more than thirty years, and is now at Stanford. Kotkin is the author of many books, including two volumes of a projected three-volume biography of Joseph Stalin.

Russia’s war against Ukraine began in 2014 with its militarized annexation of Crimea, and moved into its current phase when, in February, 2022, Vladimir Putin ordered a full-scale invasion. In the initial months of that second phase, Ukraine, under the leadership of Volodymyr Zelensky, and with support from NATO, scored some astonishing victories, including the defense of Kyiv. But, although the people of Ukraine continue to stun the world with their resilience and imagination, the war shows no sign of ending anytime soon. And, as Kotkin puts it, Ukraine is running tragically low on young men of fighting age. Meanwhile, Putin does not hesitate to throw countless Russian bodies into the meat grinder of the war.

In an interview for The New Yorker Radio Hour, Kotkin talked with me about the situation on the battlefield and the evolving politics of Kyiv, Moscow, Washington, Beijing, and beyond. He raised the possibility of a Russian “Tet Offensive” that could alter the course of the American elections. He also questioned the Biden Administration’s seeming decision to “take regime change”—a threat to Putin’s rule—“off the table.” Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity; after we spoke, I added material, with Kotkin’s permission, from a series of e-mail exchanges.

This is our third conversation during this godforsaken war, and I have a very simple question: Where are we now?

Unfortunately, Ukraine is battling. They’re fighting and dying. The courage and the ingenuity are still there. But they’re running out of eighteen-to-thirty-year-olds. The average age of the Ukrainian soldiers training in Europe at the bases in Germany or the U.K. is thirty-five and older. They’re running out of munitions. They’re running out of anti-aircraft missiles. So I’m worried. I’m very worried, because of the huge casualties and the sheer size of Russia’s population compared with Ukraine’s.

It’s obvious that losses on both sides are enormous. What do we know about specific numbers?

Ukraine does not publicly release its casualty numbers, so we don’t know the exact number. But losses are really high––tens of thousands just during the counter-offensive alone. And here’s the problem: the guy in the Kremlin doesn’t care. Ukrainian leadership can’t just sacrifice their people in big numbers. So it’s not just that the numbers are bad; it’s that one side can use bodies as cannon fodder, and the other side can’t fight like that.

What’s your understanding of the success or nonsuccess of the Ukrainian counter-offensive against Russia?

It’s like the stock market these days. Everyone says they’re a long-term investor, they’re trying to produce long-term value, and then the analyst comes along and says, “Did you make your quarterly numbers? This was where you were supposed to be, and you failed.” Sadly, this is how we’re measuring what’s happening on the battlefield. The Biden Administration, our European partners, and the Ukrainians themselves talk about how they’re in it for the long haul. But then they go to a press conference and the first question they’re asked is, How come you didn’t meet your quarterly numbers? Why is the counter-offensive so slow?

The war is nine years old. People keep asking me how it’s going to end, and I say, “Why do you think it’s going to end?”

Speaking as a historian, what can a war of that length be compared to? What is the precedent for it?

All wars that start as wars of maneuver become wars of attrition, if they last longer than three to six months. And wars of attrition go on as long as both sides have the capability and the will to fight. If you don’t destroy the enemy’s capability or the enemy’s will, you can’t win a war of attrition. Ukraine has done some things that are just breathtaking. They’ve managed to neutralize the Russian Black Sea fleet without having a navy of their own. The ingenuity continues.

The problem is that there are two key variables in a war of attrition. One is the other side’s ability to fight. You’ve got to bomb their factories and take out their munitions production. The other variable is their will to fight. And, for Russia, the will to fight is about one guy. And we have taken regime change off the table. We have said many times, publicly and privately, that we’re not going to go after Putin’s regime because we don’t want him to escalate. But, by taking regime change off the table, we’re not pushing on the will to fight. And, if we’re not hitting Russia’s capacity to fight and not hitting their will to fight, then they can go on and on.

You seem to be saying that it was a mistake for the United States to make it clear to Russia that we are not pursuing a change of regime in Moscow?

I strongly back the policy of the threat of regime change. It is the most important lever to pull in order to exert pressure on Putin, who values his own personal regime above all else. As long as Putin feels that his regime is safe, he will continue to destroy Ukraine and throw his own people to their deaths.

But I acknowledge the argument that escalation is a danger that could arise from such a policy. I think this is a worthy public debate: Would the threat of regime change lead Putin to escalate the conflict? The avoidance of a wider war has been an achievement of the Biden Administration. It’s hard to get credit for something that does not happen, but the Administration deserves credit.

That said, I still support putting pressure on Putin’s regime. We should be seeking defectors among the nationalists, military, and security people who appeal to Putin’s base. Get those people—who are willing to state publicly that the war was a mistake, that it is hurting Russia, and that Ukraine is a separate country and people—out of Russia. Get them into European capitals, and on television or YouTube. The more the merrier.

The escalation debate has been solely about what might happen, or not happen, if we send more weapons. Most analysts have dismissed the possibility of escalation at all: we refuse to send tanks because of fears of escalation, then we send them, and there’s no escalation. Ditto for airplanes. But, of course, doing things gradually helps one to understand whether there will be escalation or not. In any case, sending tanks has not been decisive, and airplanes face the challenge of Russia’s anti-aircraft batteries (S-300s and S-400s). F-16s have almost never flown against anti-aircraft batteries in their history. Tanks are far less effective without air cover. Airplanes cannot fly against saturation anti-aircraft fire, and we are not attacking Russia’s anti-aircraft batteries, many of which are on Russian soil. It would take quite something to wipe them out.