When six-year-old Adam Walsh went missing from a mall in Hollywood, Florida in 1981, local police didn’t immediately start a search, the National Crime Information Center didn’t track missing children, and it took the FBI seven days before they showed up to tell the boy’s parents that the agency wasn’t “in the kid business.”

“No one helped us in 1981, when Adam was kidnapped,” his father, John Walsh, told Newsweek. “The little Hollywood, Florida police had no idea what they were doing … They didn’t search for Adam that night. I was so worried when it got dark.”

Walsh ended up designing his own missing persons flyer and took up residence at the local police department as he launched his own search effort for his son. But it was too late. Adam Walsh’s severed head was found two weeks after he disappeared, in a drainage canal in Indian River County, Florida.

The search for America’s missing has evolved since then – and changes in technology, law enforcement approaches and involvement of civilian investigators are making a difference. Yet, as the United States marks National Missing Persons Day on February 3, the challenge remains enormous. Each year, more than 600,000 people are reported missing in America, according to the Department of Justice’s National Missing and Unidentified Persons (NamUs) database.

Newsweek is embarking on a yearlong project to raise awareness of missing persons and amplify the stories of those affected.

“With the changes that we’re seeing today, the needle has moved,” said John Bischoff, vice president of the missing children division at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. “It has moved certainly in a positive direction in terms of the speed in which we’re able to engage with the public, the speed at which we’re able to pull in lead information … And we’re seeing faster turnarounds in how quickly we are able to find missing children and get that information to law enforcement. Get that child back to a safe place,” he told Newsweek.

Yet, so many children and adults go missing every year, even this progress has not been enough to keep up.

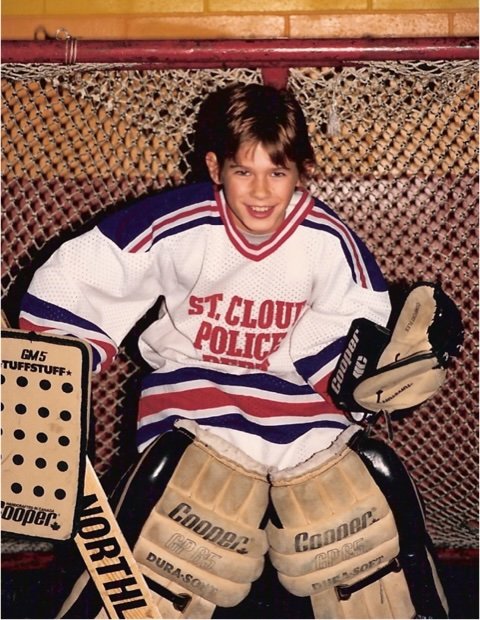

Courtesy of John Walsh

Shifting Laws and Ideas

In the decades since his son’s disappearance, John Walsh has been best known for his roles hosting TV shows, including “America’s Most Wanted” and, currently, “In Pursuit with John Walsh” on Investigation Discovery. However, Walsh is most proud of the many changes in national law that he helped to bring about, which have fundamentally shifted the way law enforcement now searches for missing children and adults.

In the years since Adam disappeared, Walsh has played roles passing a law requiring the National Crime Information Center to list missing children (previously it had included records on convicted felons and stolen cars, and the like); passing the Missing Child Assistance Act, which broadened the FBI’s role in helping investigate missing children’s cases; and creation of the AMBER Alert system. Additionally, the Adam Walsh Act, signed into law in 2006, established the sex offender registry system among other things.

With these changes, along with the creation of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a nonprofit established by Congress in 1984, of which Walsh was a founder, law enforcement has shifted its thinking and approach to missing persons cases.

One long-standing problem was that when older children and teenagers went missing, police would be inclined to categorize their disappearance as a potential runaway situation. That meant crucial hours and days could be lost before officials took the case seriously. More recently, law enforcement has increasingly shifted away from that thinking.

“Historically, missing person cases weren’t treated as a priority, but I think that’s changing now,” said Louis Barry, a former police chief in Western Massachusetts and now a volunteer investigator with Private Investigations for the Missing, a nonprofit organization that helps families search for missing loved ones.

“Police, historically, were geared towards investigating criminal activity,” he told Newsweek. “Just because someone goes missing doesn’t necessarily mean that a crime is involved. So, years ago, they weren’t given a lot of priority to investigations unless there were children involved, or unless it was an obvious kidnapping.”

Major Changes in Technology

Whether it’s DNA, digital footprints or information sharing via national clearinghouses, technology has made massive advances.

“The advancements we’ve made in DNA technology and family reference sample gathering for identification of people, have been huge strides,” Bischoff said. “From a technology standpoint, the fact that there’s digital footprints out there and more information to provide law enforcement with indicators of proof of life is a huge benefit to us. Additionally, the way we can utilize social media, and the media in general to engage with the community to get information out to the public quickly, in a time of need, is light years beyond where we were even 10 years ago.”

One of the most obvious changes in solving missing persons cases has been the introduction and improvement of DNA technology. Until roughly six years ago, law enforcement agencies were using the standard CODIS forensic DNA testing, which looks at 20 markers, said Kristen Mittelman, chief development officer for forensic DNA company, Othram.

Now, experts are using hundreds of thousands of markers for more thorough forensic work. It’s a new class of forensic methods that can capture lots of information from smaller or more problematic DNA samples.

“Unfortunately, consumer testing and medical testing is geared toward fresh blood,” Mittelman told Newsweek. “When you go to the doctor and you give blood, you have a single source DNA sample and (a greater) quantity; it’s fresh, not contaminated. All of those things make it a lot easier to run those assays. When you use forensic evidence, you have the exact opposite. You almost always have a mixture between perpetrator and victim or non-human DNA, and that leads making it a lot more difficult to build a profile that has hundreds and hundreds of thousands of markers.”

Othram has used a method called “forensic-grade genome sequencing,” which is used by federal authorities and law enforcement agencies around the country to identify victims and perpetrators.

The company was able to announce 144 identifications publicly last year and has also helped exonerate people falsely accused of crimes.

The increased level of accuracy is critical, Mittelman said: “DNA testing is a destructive process… Every time you run a sequencing reaction, you’re consuming the evidence.”

Which means, in the past, the last bits of DNA evidence could be destroyed through weaker DNA testing processes – without yielding meaningful results.

“The evidence would be consumed and you wouldn’t get an answer, and someone would lose their chance for justice,” she said. “A family member would lose their chance to find out what happened to their loved one and there will be loss of closure. That’s why we saw the urgency in jumping in and creating technology that was purpose-built for forensics, so that every case can have the maximum chance of success.”

Another key development was the establishment of The National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs).

NamUs is a national clearinghouse for information about missing, unidentified, and unclaimed persons cases in the United States. Established in 2005, it allows case information to be shared and compared across jurisdictional boundaries. In addition to law enforcement, it has been used by medical examiners and family members searching for a missing person.

The system is user-friendly and allows users to cross-reference searches based on key case criteria, said Charles Heurich, a senior physical scientist at NamUs.

“For example, if you were working a missing persons case and the best friend of a missing person said, ‘last time I saw them was Friday night and they got into a red Mustang with someone I don’t know,’ you could potentially type in ‘red Mustang.’ And that would come up if there were any other cases where there was a red Mustang that was involved,” Heurich told Newsweek.

In another example, Heurich recalled a woman who located the remains of her missing sister by searching for her specific combination of unique tattoos. The young woman had gone missing in Kansas City, Missouri, yet her body was discovered in Western Ohio. Decades ago, it would have been inconceivable to make such connections.

The NamUs system has helped resolve 39,334 missing persons cases and 6,978 unidentified persons cases. It also offers free investigative support and forensic services for missing persons cases across the country.

Civilian Involvement

Another more recent evolution in the search for missing persons has been the introduction of civilians. Law enforcement agencies across the country have hired lay people – often former law enforcement – to help with research and case management, or to help stay in touch with family members on what’s going on with their loved ones’ case.

“That never happened before,” said Barry, who has been tapped by law enforcement to help with these cases. “There’s really been a lot of changes in how police handle these cases.”

“There’s a department out in Ohio that actually was so overwhelmed with cold cases that they assigned a full-time detective to the cases. This cold case squad then hired a bunch of retired detectives to help on a part time basis. So different departments are doing things differently. And some departments are not doing anything at all.”

For example, the Phoenix Police Department revealed last month that they dissolved their cold case department altogether. As in many departments, the resources are too few and the workload is too large.

That’s where civilian support can come in handy. The Denver Police Department launched a program in January to add more civilian resources to assist their investigative detectives in finding missing kids, Bischoff said.

Vermont State Police had Barry help them when they were investigating the disappearance of 17-year-old Brianna Maitland, said Detective Lieutenant John-Paul Schmidt, of the department’s Major Case Unit, which sometimes pursues high-profile missing persons cases.

The benefit is, there’s “now another asset that’s looking into the case, that’s going out and trying to contact people and scratching the surface a little, to see if information can be developed,” Schmidt told Newsweek. “He communicates with us. If there’s something that’s maybe going to be detrimental, he’ll consult with us before he takes certain steps. Just because there’s some actions that would be better if they were taken by a sworn law enforcement official versus a civilian.”

Beyond the civilians directly working with police, a growing wave of keyboard warriors have built communities in online true crime forums where they work together to share theories and attempt to solve missing persons cases. Sometimes these communities develop valuable leads – in the case of 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling, an internet blogger played a huge role in keeping the case visible and pushing toward new leads.

“They can be a blessing and a curse,” said Bischoff, of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. “If managed correctly, they’re an absolute blessing. Because they help keep the case in the public eye. They help keep research moving forward on the case – if they’re passing their information directly to law enforcement … It can be a curse if they’re looking at leads law enforcement may have looked at last year or even five years ago. It can be a problem if it’s not organized properly.”

Profound Loss

The loss of a family member – particularly a child – is a devastation that no one should have to go through, said Patty Wetterling, chair of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Courtesy of Patty Wetterling

Her son, Jacob, was kidnapped Oct. 22, 1989 from his hometown of St. Joseph, Minnesota.

“There is nothing like having a missing child,” she told Newsweek. “The nightmares are horrible. And you feel so helpless. You really don’t get to go out and search. I was calling all my friends and telling him to come over and we needed to search, and law enforcement said, ‘you need to stay here, what if Jacob calls?’ So I was stuck. Wanting to help but unable to help in the physical search. It is a horrific thing.”

Jacob’s killer, Danny Heinrich, led police to his remains on Sept. 1, 2016, in a pasture near Paynesville, Minnesota – about 30 miles from where the boy was abducted.

“The hope was real to me,” Wetterling said. “There was a chance that Jacob could still be out there, and I hung on to that. In my heart, I believed there was a chance and I hung on to that until he was found. And then, it was it was like he was stolen all over again. For our family, he wasn’t coming home, and we had to deal with that.”

Wetterling has found purpose in the years since through her work with the center.

“I would like parents to not be afraid,” she said. “Because if you give your children empowerment tools and information they’re not likely to be abducted – and scared kids are not safer. Scaring children is not a good thing.”

She noted that the emphasis on “stranger danger” often misses the mark, because statistically children are more likely to be harmed or abducted by someone who is close to the family.

“I would encourage parents to learn about it and know how to talk to your kids age, appropriate discussions are helpful, not hurtful,” Wetterling said.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.