There is a renewed push in Washington to ratify an international agreement on oceanic conduct and maritime resources.

Proponents warn that failing to ratify the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) means giving up strategic mineral reserves that are valued in the trillions of dollars and key to national security. Opponents say the treaty would threaten U.S. sovereignty and waste taxpayer dollars.

Nicknamed the “constitution of the oceans,” UNCLOS was signed in 1982 and went into force 12 years later. Though the U.S. government adheres to the spirit of the treaty on the international stage, the document has yet to make it to the Senate floor for a full vote, despite widespread support in the military and diplomatic corps and presidents from both parties.

Last month, more than 300 former officials—including legislators, cabinet members, diplomats and military leaders—signed an open letter to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee leadership urging adoption of the treaty.

Jam Sta Rosa/AFP via Getty Images

“In the decade since the Law of the Sea Treaty was last considered by the Senate, China and Russia have taken advantage of our absence to work actively to undermine critical United States economic and national security interests,” the letter said.

Without ratification, the U.S. cannot take a seat at the International Seabed Authority, the Kingston, Jamaica-headquartered U.N. organization established by UNCLOS that regulates deep-sea exploration and mining of natural resources.

The letter said the country has already lost out on two of four deep seabed mine sites it could have claimed, each with an estimated trillion dollars’ worth of strategic minerals like copper, rare earths, cobalt, nickel, and manganese, “minerals critical for United States security dominance as well as the transition to a greener twenty-first century.”

“UNCLOS is a fatally flawed treaty,” Steven Groves, Margaret Thatcher fellow at the Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom at The Heritage Foundation, told Newsweek. “Joining the convention would result in a dangerous loss of American sovereignty. It would require the U.S. Treasury to transfer billions of dollars to an unaccountable international organization in Jamaica, which in turn is empowered to redistribute those American dollars around the world.

The Heritage Foundation and other conservative advocacy groups were considered instrumental in rallying enough opposition during the last attempt at ratification, in 2012, before the treaty reached the Senate floor for a full vote.

“Strategically, the U.S. failure to ratify a treaty it helped negotiate and which has been almost universally embraced by the international community undermines its claim to defend the rules-based order,” Greg Poling, director of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank in Washington, D.C., told Newsweek.

“Economically, the U.S. failure to ratify has left it out of the International Seabed Authority and prevented it from filing an extended continental shelf claim even as deep seabed mining is about to become a reality, so U.S. companies get to sit on their hands as China leads the way on a major new industry.

Moving forward with the treaty would also lend Washington more credibility in its critiques of China’s long-running territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas.

“Ratifying UNCLOS would shore up U.S. allies’ confidence in the United States; it would remove a People’s Republic of China talking point that the U.S. says it supports the rules-based order but won’t sign up to the rules,” Bonnie Glaser, managing director of the Indo-Pacific Program at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, told Newsweek.

Newsweek reached out to the Chinese Foreign Ministry for comment.

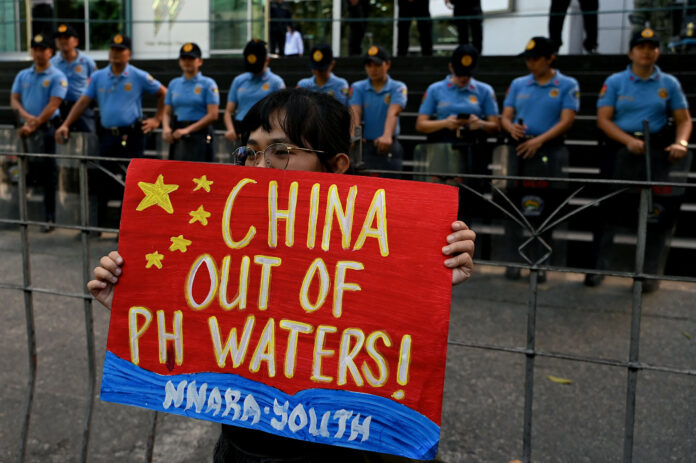

China’s sweeping claims over the South China Sea include areas within neighboring countries’ exclusive economic zones. Under UNCLOS, coastal states are afforded the sole right to resources within these 200-nautical-mile (230-mile) zones.

The Philippines brought its dispute with China before the Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration, where a tribunal in 2016 sided with the Philippines, citing UNCLOS. China refused to take part in the proceedings or accept the decision.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.