Is it the end of the world if Kirsten Dunst isnât around to witness it? Iâm beginning to wonder. At the mystical aliens-among-us climax of Jeff Nicholsâs âMidnight Specialâ (2016), it is Dunst, aglow with Spielbergian wonderment, who compels our surrender to the thrill of the unknown. In Lars von Trierâs end-of-days psychodrama, âMelancholiaâ (2011), Dunst, giving her greatest performance, all but wills her clinical depression into a cataclysmic reality. And Iâm tempted to throw in Sofia Coppolaâs âThe Beguiledâ (2017), an intimate Civil War gothic in which Dunst, as a dour Virginia schoolteacher, distills the existential gloom of the moment into every shattered stare. It may not be Armageddon, but, from her terrified vantage, whoâs to say that tomorrow is another day?

A very different civil war swirls around Dunst in âCivil War,â a dystopian shocker set in a not too distant American future. The English writer and director Alex Garland has an undeniable flair for end-times aesthetics, and he and his cinematographer, Rob Hardy, rattle off image after unsettling image of a nation besieged. Their camera lingers on bombed-out buildings, blood-soaked sidewalks, and, in one surreal tableau, a highway that has become a vehicular graveyard, with rows of abandoned cars stretching for miles. Plumes of smoke always seem to be rising from somewhere in the distance, and apart from a few congregation zonesâa makeshift campsite where kids play with abandon, a crowded block where desperate Brooklynites line up for water rationsâthe landscapes are eerily emptied out. At night, a deceptive stillness sets in, and the sky lights up, beautifully, with showers of orange sparks. We could be watching fireflies at dusk, if the hard pop of gunfire didnât warn us otherwise.

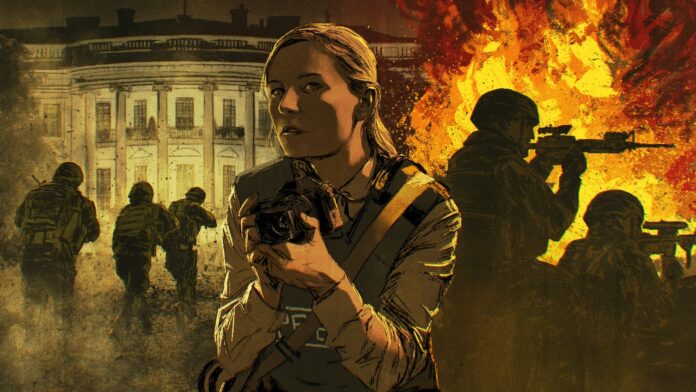

Strictly as a piece of staging, âCivil Warâ is as vividly detailed a panorama of destruction as Iâve seen since âChildren of Menâ (2006), or perhaps the Garland-scripted zombie freakout of â28 Days Laterâ (2002). Even Dunst has never stared down a more imposing visionâand stare it down she does, invariably through the lens of a camera. Her character, Lee, is a skilled photojournalist, and if your mind doesnât automatically leap to Lee Miller, celebrated for her stunning images of the Second World War, rest assured that Garlandâs script is eager to connect the dots. This Lee may not have her namesakeâs celebrity glamour or her willingness to turn the camera on herself. But Dunst gives the character a comparable steeliness, a cut-the-crap professionalism that gets you immediately on her side. She has fearlessly covered sieges, firefights, and humanitarian crises the world over; now, with a tightly set jaw and an unwavering seriousness of purpose, sheâs confronting the horror in her own back yard.

The plot comes at us in a rush of details so clipped and vague that you canât help but suspect that theyâre largely irrelevant. In a fanciful twist, Texas and California have cast their red-blue animus aside and forged the Western Forces, a secessionist axis seeking to topple the President (the ruthless, mirthless Nick Offerman), a despot who has appointed himself to a third term. Florida, not to be outdone, has launched a separatist campaign, too. In response, the President has called in his troops and launched air strikes against American citizens. With these militarized factions attacking one another relentlessly, the entire country has descended into poverty and lawlessness, and Lee has seen and photographed it all. Now she sets her sights on the White House, where it seems that the conflict will finally end, with the President cornered and overthrown.

But, first, thereâs a treacherous road to travel from New York to Washington, D.C. Along for the ride are two reporters: Joel (Wagner Moura), who tempers his cynicism with a wolfish grin, and Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson), a distinguished political writer whose instincts are as sturdily old-school as his suspenders. Then, thereâs Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), the youngest and most surprising addition to the group. Sheâs an aspiring photographer who idolizes Lee (both of them) and, like many a plucky outsider, becomes a de-facto stand-in for the audience. Jessie is talented, serious-minded, with a puristâs preference for black-and-white film. She is also reckless and naïve, and Lee is infuriated by her presence on this dangerous mission. Lee has already saved her life once, in an early scene, yanking her out of harmâs way shortly before a bomb explodes, leaving behind streams of blood and mangled body parts. There is more carnage to come, and Lee knows that Jessieâindeed, all of themâmight not survive.

This isnât the first time Garland has sent a small group of courageous folk on a perilous journey. Thatâs more or less the premise in his screenplays for â28 Days Later,â the space thriller âSunshineâ (2007), and the terrifying âAnnihilationâ (2018), his second feature as a writer-director. (He also wore both hats on âEx Machinaâ and âMen.â) We accept these premises because we accept the conventions of genre, and because the stories themselves, for all their visceral grip, stake little claim to real-world verisimilitude. But âCivil Warâ has loftier ambitions; its parable of American infighting means to sound a note of queasy alarm, as if we were just one secessionist screed or Presidential abuse of power away from tumbling into a comparable nightmare.

Why, then, despite the sweep and scale of Garlandâs world-building and world-destroyingâand with an election-year release titled âCivil Warââdo we remain at armâs length, engaged yet unconvinced? As the four principal characters make their way south, they bear witness to an America gone unsurprisingly mad. But, even when a knot forms in the pit of your stomach, youâre more persuaded by the tautness of Garlandâs craft, the skill with which he modulates suspense and dread, than by his understanding of how such an immense catastrophe might really play out. Whenever the mood lightens, you know, instinctively, that a tragic swerve is right around the corner. When Lee and her companions are ambushed at an abandoned Christmas theme-park display, your terror is held in check by the winking nastiness of the setupâand thatâs before a lawn Santa catches a bullet in the face. The movieâs most chilling sequenceâin a nicely demented touch, Jesse Plemons, Dunstâs offscreen husband, pops up as a murderous psychopathâis also its most dubiously contrived. Was it really necessary to introduce and then immediately sacrifice two nonwhite characters to score a point about the racism that lurks in Americaâs heartland? Itâs not the only question Garland leaves unanswered.

The point, if âCivil Warâ has one, is that war is not only hell but also addictive, and that, for an alarming swath of the population, the joy of meting out rough justice with a rifle outstrips any deeper moral or ideological convictions. But war coverage has its own allure, and before long Jessie is hooked; the more field experience she gets, the more indelible the rush. In skirmish after skirmish, she masters the tools of her trade and inures herself to the trauma that comes with using them. As bullets whiz by and tanks roll past, she learns what it means to embed oneself, to capture dramatic images without interfering, to risk everything for the sake of the shot. (The scenes of photographers at work are often set to jarringly irreverent needle drops; a blast of De La Soul seems to captureâand interrogateâthe desensitization their job demands.)

As a tribute to the work that journalists do, âCivil Warâ feels entirely sincereâbut even here the fuzziness of Garlandâs execution undermines his nobler intentions. What outlets and platforms are Lee and her colleagues using to disseminate that work? The media industry, a disaster zone even in peacetime, appears to have collapsed. Internet connections are spotty to nonexistent, and the conflict rages, for better or worse, without the breathless incursions and distortions of social media. One character makes wry reference to âwhatever is left of the New York Timesâ; another notes that in the U.S. Capitol journalists are treated as enemy combatants and shot on sight. Such demonization of the press, with its grim echo (or harbinger?) of Trumpist rule, is about as close as the movie gets to advancing a remotely political point of view. The more arresting its doomsday imagesâa daring raid on the White House, a fiery assault on the Lincoln Memorialâthe more Garlandâs war loses itself in a nonpartisan fog, a thought experiment that short-circuits thought.

That doesnât mean it isnât amusing, as the credits roll on the appalling final tableau, to speculate about the aftermath. Will the Western Forces be required to make state-specific concessions in order to maintain their rickety alliance? Will California start banning books if Texas relaxes its abortion laws? I have a sneaking suspicion that Florida presses on with its own fight for independence, and in so doing ushers in the warâs next phase. If at first you donât secede, try, try again. â¦