Fragments of an almost 1,000-year-old lost manuscript have been uncovered, and it may have belonged to a princess who fled England after the country was conquered by the Normans in the 11th century.

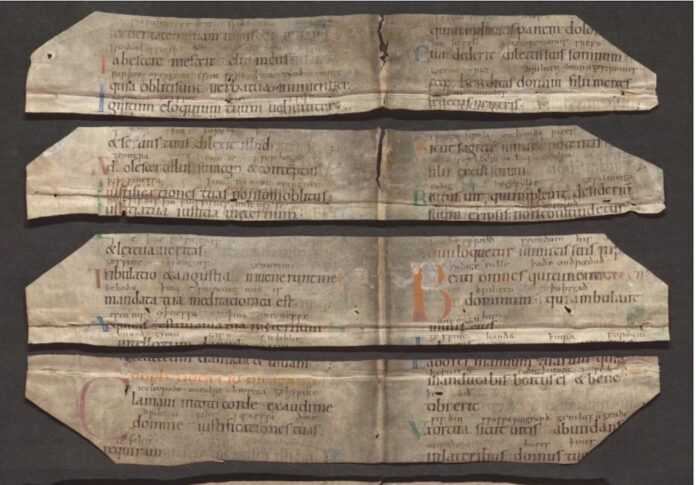

Researcher Thijs Porck identified 21 fragments of the manuscript, which were found in an archive in the city of Alkmaar in the Netherlands, according to a study published in the journal Anglo-Saxon England. In the study, Porck, who is at Leiden University, describes the discoveries while also analyzing their provenance and the text contained in them.

Intriguingly, the parchment fragments were found within the bindings of a four-volume Greek dictionary. They had been used to reinforce the bindings of the scholarly work, which was bound in a Dutch workshop around A.D. 1600, Porck’s research has shown.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, bookbinders sometimes used parchment to strengthen their book bindings. Because this material was expensive, people often chose to cut up old manuscripts from the earlier medieval period.

Regionaal Archief Alkmaar

The manuscripts that were chosen for this use were often ones that had lost their value—for example, those that were associated with Catholicism or written in a language that could no longer be read.

The discovery of the manuscript fragments was largely “accidental,” Porck, an associate professor of medieval English, told Newsweek. Staff at the Regional Archive Alkmaar had sent him images of the fragments, which they had uncovered during a survey of early modern book bindings in their collection that features medieval parchment.

“I drove to the archive the next day and was very happy to see that it was not just one fragment but 21 fragments. That was the start of a fascinating research journey that took more than a year and a half to complete,” Porck said.

The fragments found in the Alkmaar archive are from a Latin language manuscript that contains additional notations written in Old English. These annotations—known as “glosses”—are often found in medieval texts, inserted between the lines or in the margins of the primary text, primarily to explain foreign or difficult words.

Old English, or Anglo-Saxon, is a West Germanic language that was spoken in Britain between roughly A.D. 500 and 1100. The earliest recorded form of the English language, it is very similar to German, Frisian and Dutch.

In the Alkmaar manuscript fragments—which come from a Psalter (a volume containing the biblical Book of Psalms)—Old English is written above every Latin word to help explain the text. This probably had a didactic purpose: Any reader of the Psalter could have used it to learn Latin. Porck managed to date the 21 fragments to 1050-1075 on the basis of its script.

“The interlinear Old English gloss makes it a very interesting find because it is relatively rare to find materials in this language,” Porck said. “I could reconstruct some leaves of the Psalter, and, when it was complete, it must have been a beautiful and luxurious book.”

He continued: “What made this find even more interesting was the fact that, on the basis of script, language, size and contents, these fragments could be linked to others found throughout Europe: in Cambridge, England; Haarlem, the Netherlands; Sondershausen, Germany; and Elbląg, Poland. These fragments, scattered all over Europe, had once been part of the same manuscript.”

Porck established that many of these fragments came from books that were bought and bound in the Dutch town of Leiden around the year 1600. But how did a Dutch bookbinder in the year 1600 come to own an 11th-century manuscript from England?

It is known that around the mid-16th century, manuscripts from England were shipped to the European mainland in large quantities—when the belongings of English monasteries were confiscated—so they could be reused by bookbinders and soap makers. One possibility is that the 11th-century manuscript was one of these. But Porck also proposes another idea.

Very excited to announce the discovery of Old English fragments inside a series of book bindings! They come from an 11th-c. Latin psalter with Old English glosses and this psalter comes with a fascinating potential backstory involving a refugee English princess! 🧵 pic.twitter.com/43a2bT4NOo

— Thijs Porck (@thijsporck) January 11, 2024

The second hypothesis suggests that the manuscript represents a long-lost Psalter that belonged to an English princess called Gunhild who fled her country to the Continent after the Norman Conquest, which began in 1066. Gunhild was the sister of the defeated English king Harold Godwinson, who was killed at the Battle of Hastings that year.

Gunhild died in Bruges, Belgium, in 1087, with her Psalter and other belongings donated to the St. Donaas Catholic church in the city. The last documented mention of the manuscript at the church was in 1561, with a text from that year describing it as the Gunhild Psalter, written in Latin, “but with explanations in the Saxon language, which no one here can quite understand.”

Since then, there has been no trace or mention of the Psalter. But Porck managed to determine that the books of the church were confiscated by Calvinists, followers of a major denomination of Protestantism, in the year 1580.

The Calvinists founded a public library with the books they deemed to be useful, but those considered to be unnecessary were sold. A Catholic Psalter with incomprehensible glosses, like Gunhild’s copy, would likely have belonged to the latter category.

“Perhaps this is how Gunhild’s Psalter ended up in the workshop of a Leiden bookbinder in 1600, and the fragments that were now discovered in Alkmaar may have been part of her personal copy of the Psalms,” Porck said.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.