An “extraordinary” prehistoric site that has been described as “Britain’s Pompeii” has revealed unprecedented insights into the lives of people during the late Bronze Age.

Investigations at the site—located in Must Farm quarry near the city of Peterborough in Cambridgeshire, eastern England—since its initial discovery in 1999 have uncovered the exceptionally well-preserved remains of a stilt village that was constructed around 850 B.C.

The prehistoric settlement was raised on stilts above a now defunct, slow-moving river in a marshy region known as the Fens. But evidence suggests the village was destroyed be a catastrophic fire when it was less than a year old, with the buildings and their contents collapsing into the muddy river below.

A fortuitous combination of factors, including charring from the fire, waterlogging, and burial in oxygen-depleted silts, resulted in the remarkable preservation of structures and artifacts in the location where they fell, leaving behind a time capsule that yielded fascinating insights into the settlement.

Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Now a pair of reports have outlined in detail findings from the site made by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) during a full-scale excavation conducted in 2015-2016.

The excavation revealed a “uniquely preserved group of wooden domestic structures, unparalleled in the quality of their architectural detail”—not to mention thousands of artifacts—the authors of the report wrote. They described Must Farm as “one of the most extraordinary Bronze Age sites” in Europe.

The latest reports reveal in unprecedented clarity the surprisingly sophisticated domestic lives of the Bronze Age Britons who resided in the settlement, casting light on their home interiors, the animals they kept and the clothes they wore, among other aspects of daily life.

“This is a fantastic example of what daily life would have been like in the Late Bronze Age, which allows us to connect with the residents of the site and see what they were eating, what tools and technologies they were using, and even their health,” CAU project archaeologist Chris Wakefield told Newsweek.

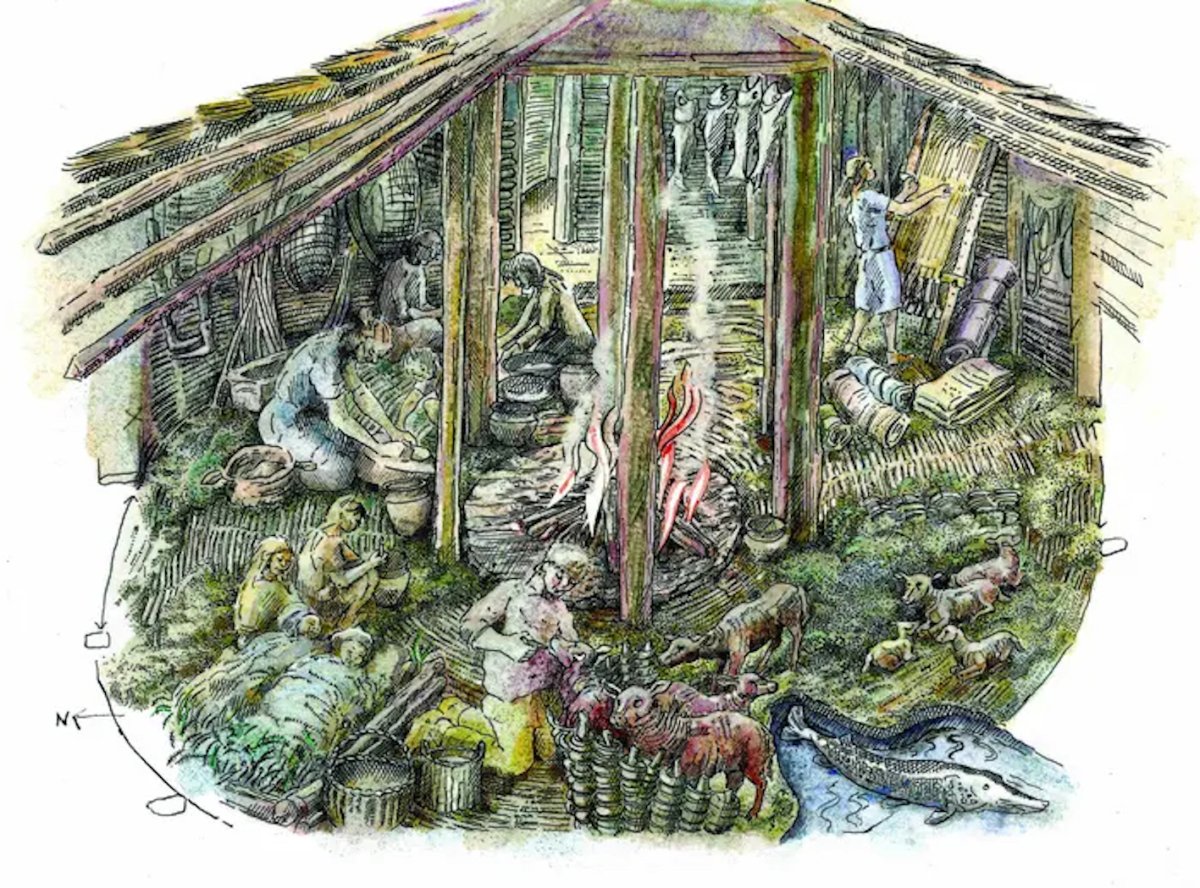

At the site, archaeologists unearthed the remains of four large wooden roundhouses and a square entranceway structure, all of which were constructed on stilts. Raised walkways connected some of the main houses, and the village was surrounded by a fence of sharpened wooden posts measuring around 6 feet in height. The original settlement was likely twice as big as it appears, though—half of the site was removed by quarrying in the 20th century—and may have housed up to 60 people.

The reports indicate that the Bronze Age people of the Fens had a surprisingly comfortable lifestyle. Their houses, for example, featured distinct zones of activity that were comparable to “rooms” in modern homes.

“Some of the highlights are that this site has given us the opportunity to ‘see inside’ Bronze Age homes. The circumstances of the site’s destruction and the preservation conditions have allowed us to see how space was used,” Wakefield said. “For example in Structure 1 we’re able to see kitchen and cooking spaces in the northwest of the building, textile production in the southeast, an area where lambs were living in the southwest and a sleeping space in the northwest.”

“This is such a rare opportunity to see these ‘rooms’ inside a home from around 850 B.C. Another exciting discovery is that the deposition of material means we’re able to look at what an everyday home from almost 3,000 years ago in the Fens would have contained. Seeing how much stuff would have been used and kept inside the houses and the quantities that they were found in,” he said.

Evidence has shown that each roundhouse roof had three layers—insulating straw covered by turf and clay—making it warm and waterproof but still well-ventilated, contributing to the surprising levels of comfort.

“In a freezing winter, with winds cutting across the Fens, these roundhouses would have been pretty cosy,” Wakefield said in a press release.

Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Among the highlights of the remains discovered at the site were preserved textiles that the researchers said were the finest such examples of this period in Europe.

The team also found a cache of spears measuring up to around 11 feet in length, as well as swords. These weapons may have been used for defensive purposes or to hunt animals. An intact hafted axe was also uncovered, which had been placed directly in the silt beneath Structure 1. The researchers believe this was perhaps a token of good fortune, or served as an offering to some kind of spirit on completion of the construction.

“This is easily the most exciting excavation I have ever been part of,” Wakefield told Newsweek. “Every day we never knew what amazing artifacts were going to emerge from the ground, from the most delicate preserved textiles to hafted spears.”

Other highlights include human fossilized feces, some of which contained parasite eggs, indicating that the inhabitants struggled with intestinal worms. The discovery of several small dog skulls at the site suggests the Fen folk kept these animals domestically, possibly as pets but also for hunting purposes.

Judith Dobie/Historic England

A pottery bowl with the finger marks of its maker captured on the clay was found still holding the remains of a meal—a wheat-grain porridge mixed with animal fats. This sheds light on the moment that the inhabitants had to abandon their homes to escape the fire.

While there is no evidence of any people dying in the blaze, archaeologists did find some human remains at the site, including the skull of an adult woman that had been polished by repeated touch, a possible sign that it was a memento of a deceased loved one.

After the fire, it is feasible that the residents simply constructed a new settlement in a different location.

“A settlement like this would have had a shelf-life of maybe a generation, and the people who built it had clearly constructed similar sites before. There is every possibility that the remains of many more of these stilted settlements are buried across Fenland, waiting for us to find them,” David Gibson, archaeological manager at CAU and a co-author of the report, said in the press release.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.